NOTE: Anyone who has seen several derogatory articles about me on the web and is curious about what the real story is, please read this and this.

Dr. Martin Makary claims that medical errors are now the third leading cause of death in the US. Is he correct?

It is an unquestioned belief among believers in alternative medicine and even just among many people who do not trust conventional medicine that conventional medicine kills. Not only does exaggerating the number of people who die due to medical complications or errors fit in with the world view of people like Mike Adams and Joe Mercola, but it’s good for business. After all, if conventional medicine is as dangerous as claimed, then alternative medicine starts looking better in comparison.

In contrast, real physicians and real medical scientists are very much interested in making medicine safer and more efficacious. One way we work to achieve that end is by using science to learn more about disease and develop new treatments that are as efficacious or more so than existing treatments with fewer adverse reactions (clinical equipoise). Another strategy is to use what we know to develop quality metrics against which we measure our practice. Indeed, I am heavily involved in just such an effort for breast cancer patients. Then, of course, we try to estimate how frequent medical errors are and how often they cause harm or even death. All of these efforts are very difficult, of course, but perhaps the most difficult of all is the last one. Estimates of medical errors depend very much on how medical errors are defined, and whether a given death can be attributed to a medical error depends very much on how it is determined whether a death was preventable and whether a given medical error led to that death.

Some cases are easy. For example, if I as a surgeon operating in the abdomen were to slip and put a hole in the aorta, leading to the rapid exsanguination of the patient, it’s obvious that the error caused the patient’s death. But what about giving the wrong antibiotic in a septic patient who is critically ill with multisystem organ dysfunction? Other examples come to mind. When should a given medical error in such a critically ill patient who has a high probability of dying even with perfect care be blamed if that patient dies? It’s not a straightforward question.

Perhaps that’s why estimates of the number of deaths due to medical error tend to be all over the map. Consider this. According to the CDC, there are approximately 2.6 million deaths from all causes in the US every year. Now consider these headlines from last week:

- “Medical Errors Are No. 3 Cause Of U.S Deaths, Researchers Say (NPR)”

- “Researchers: Medical errors now third leading cause of death in United States” (The Washington Post)

- “Why Are Medical Mistakes Our Third Leading Cause of Death?” (Huffington Post)

- “Second study says medical errors third-leading cause of death in U.S.” (USA TODAY)

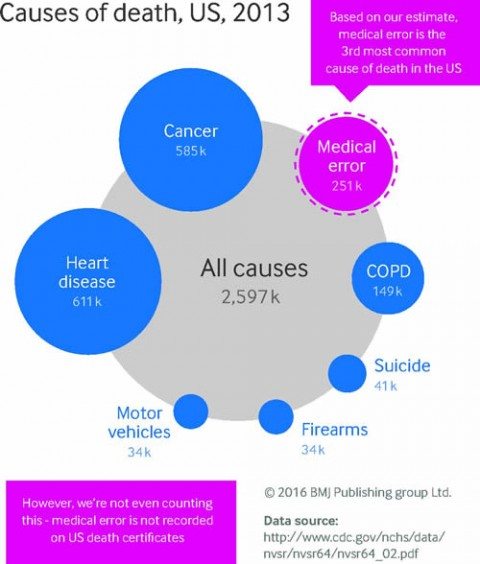

These stories all refer to an article last week in BMJ by Martin A Makary and Michael Daniel entitled “Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US,” which claims that over 251,000 people die in hospitals as a result of medical errors. Given that, according to the CDC, only 715,000 of those deaths occur in hospitals, if Makary and Daniel’s numbers are to be believed, some 35% of inpatient deaths are due to medical errors. That’s just one reason why there are a lot of problems with this article, but there are even more problems with how the results have been reported in the press and the recommendations made by the authors.

Error inflation?

The first thing I noticed that surprised me about this BMJ article is that it isn’t a fresh study at all. Rather it’s a regurgitation of already existing data. It is not a “second study,” as, for example, the USA TODAY headline calls it. It’s just a pooling of existing data to produce a point estimate of the death rate among hospitalized patients reported in the literature extrapolated to the reported number of patients hospitalized in 2013 based on four major existing studies since the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report “To Err Is Human” in 1999. Basically, it’s not unlike a similar pooling and extrapolation of studies performed by John James in 2013. Yet, in every article I’ve seen about it, it’s described as a study. In reality, it’s more an op-ed calling for better reporting of deaths from medical errors, with extrapolations based on studies with small numbers. That’s not to denigrate the article just for that. Such analyses are often useful; rather it’s to point out how poorly this article has been reported and how few seemed to notice that this article adds exactly nothing new to the primary scientific literature.

Here’s a passage from Dr. Makary’s article that disturbed me right off the bat:

The role of error can be complex. While many errors are non-consequential, an error can end the life of someone with a long life expectancy or accelerate an imminent death. The case in the box shows how error can contribute to death. Moving away from a requirement that only reasons for death with an ICD code can be used on death certificates could better inform healthcare research and awareness priorities.

Case history: role of medical error in patient death

A young woman recovered well after a successful transplant operation. However, she was readmitted for non-specific complaints that were evaluated with extensive tests, some of which were unnecessary, including a pericardiocentesis. She was discharged but came back to the hospital days later with intra-abdominal hemorrhage and cardiopulmonary arrest. An autopsy revealed that the needle inserted during the pericardiocentesis grazed the liver causing a pseudoaneurysm that resulted in subsequent rupture and death. The death certificate listed the cause of death as cardiovascular.

This example is nowhere near as straightforward an example as the authors appear to think it is. In fact, it’s an utterly horrible example. For one thing, notice the weasel wording. We’re told that the the patient was evaluated with “extensive tests, some of which were unnecessary, including a pericardiocentesis.” This implies that the pericardiocentesis wasn’t necessary, but an equally valid interpretation is that it was just one of the tests. Besides, without a lot more details, it’s impossible to tell whether the pericardiocentesis was necessary or not. While the point that the percutaneous procedure contributed to this patient’s death is valid, how do we classify this? Delayed bleeding is a known complication of percutaneous procedures, as is damage to adjacent organs that are potentially in the path of the needle. Even when done by expert hands, such procedures will cause significant bleeding in some patients and even death in a handful. When such bleeding occurs, that does not necessarily mean there was a medical “error.” It might, but even in this case, I can’t help but point out that most injuries to the liver by a percutaneous needle heal themselves. Indeed, ultrasound- or CT-guided liver biopsies are performed using much larger needles than any needle used for a pericardiocentesis, and bleeding is uncommon. (One study pegs it at 0.7%.) It was unfortunate indeed that this patient developed a pseudoaneurysm. Of course, this death might have been due to medical error. Perhaps the physician doing the procedure didn’t take adequate care to avoid lacerating the liver. We just don’t know. Given that the vast majority of bleeding after percutaneous procedures can’t be attributed to medical error, if you define any such bleeding complication as medical error, you’re going to vastly overestimate the true rate of medical error.

So let’s take a look at the some of the most cited studies that make up the data used by Makary and Daniel for their commentary.

The IOM Report: To Err Is Human

This was an issue in the IOM study, To Err Is Human. This study dates way, way back to 1999 and estimated that between 44,000 and 98,000 deaths could be attributed to medical error. The IOM came by its estimate by examining two large studies, one from Colorado and Utah, and the other conducted in New York, that found that adverse events occurred in 2.9% and 3.7% of hospitalizations and that in Colorado and Utah 6.6% of those adverse events led to death, as compared to 13.6% in New York hospitals. In both of these studies, it was estimated that over half of these adverse events resulted from medical errors and therefore could have been prevented. Thus, when extrapolated to 33.6 million admissions to US hospitals in 1997, the results of the IOM study implied that between 44,000 and 98,000 Americans die because of medical errors.

To be honest, I didn’t have that big of a problem with the IOM study. I thought it was a bit too broad in defining what constituted a medical error. Indeed, one of the authors of one of the studies used by the IOM related in a New England Journal of Medicine article in 2000:

In both studies, two investigators subsequently reviewed the data and reclassified the events as preventable or not preventable. Preventability is difficult to determine because it is often influenced by decisions about expenditures. For example, if every patient were tested for drug allergies before being given a prescription for antibiotics, many drug reactions would be prevented. From this perspective, all allergic reactions to antibiotics, which are adverse events according to the studies’ definitions, are preventable. But such preventive testing would not be cost effective, so we did not classify all drug reactions as preventable adverse events.

In both studies, we agreed among ourselves about whether events should be classified as preventable or not preventable, but these decisions do not necessarily reflect the views of the average physician and certainly do not mean that all preventable adverse events were blunders. For instance, surgeons know that postoperative hemorrhage occurs in a certain number of cases, but with proper surgical technique, the rate decreases. Even with the best surgical technique and proper precautions, however, a hemorrhage can occur. We classified most postoperative hemorrhages resulting in the transfer of patients back to the operating room after simple procedures (such as hysterectomy or appendectomy) as preventable, even though in most cases there was no apparent blunder or slip-up by the surgeon. The IOM report refers to these cases as medical errors, which to some observers may seem inappropriate.

Certainly, most surgeons consider this inappropriate. Postoperative hemorrahge is a known complication of any surgery. Many times, when a surgeon takes a patient back for postoperative hemorrhage, no specific cause is found, no obvious blood vessel untied off for example. The very definition of medical errors used in many of these studies will inflate the apparent rate. Physicians know that not every adverse event is preventable or due to medical error. However, choices on how to define medical errors had to be made, and, given the difficulty in determining which adverse events (like postoperative bleeding) are due to physician error, system error, or just the plain bad luck of being the patient for whom an accepted potential complication or adverse event happens, it’s not surprising that a simpler definition of “medical error” is preferred by many investigators.

For all its flaws and the awful “doctors are killing lots of patients” reporting that it provoked, reporting that frustrated many of the investigators who carried out the IOM study because it distracted from the true message of the report, which was to encourage further investigation and a “culture of safety” in hospitals to improve the safety of patient care, the IOM report does deserve a lot of the credit for sparking the movement to improve quality and decrease medical errors over the last 17 years. At the time, I tended to agree with IOM panel member Lucian Leape, MD, who pointed out that, even if the IOM report did greatly overestimate the number of deaths due to medical errors, “Is it somehow better if the number is only 20,000 deaths? No, that’s still horrible, and we need to fix it.” Exactly.

Classen et al: Quadrupling the IOM number

In 2004, another study was published by David Classen et al involving three tertiary care hospitals using, among other measures, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Global Trigger Tool. This study found from four to ten times the number of deaths attributable to medical error than the IOM did; i.e., approximately 400,000 per year. If this were true, then medical errors would be approaching the number two cause of death in the US, cancer, which claims 585,000 people per year.

Classen et al noted that adverse event tracking methods that had frequently been in use at the time of the IOM report missed a lot of adverse events, noting that this tool found up to ten times as many adverse events. This is, of course, not surprising because, regardless of industry or topic, any voluntary reporting system of bad things is going to underreport those bad things. People don’t like admitting that something bad happened; it’s human nature. As a result, after the IOM report, investigators tried to develop automated tools to mine either administrative data (data reported to insurance companies for purposes of reimbursement) for discharge codes that correlate with adverse events:

The Global Trigger Tool uses specific methods for reviewing medical charts. Closed patient charts are reviewed by two or three employees—usually nurses and pharmacists, who are trained to review the charts in a systematic manner by looking at discharge codes, discharge summaries, medications, lab results, operation records, nursing notes, physician progress notes, and other notes or comments to determine whether there is a “trigger” in the chart. A trigger could be a notation indicating, for example, a medication stop order, an abnormal lab result, or use of an antidote medication. Any notation of a trigger leads to further investigation into whether an adverse event occurred and how severe the event was. A physician ultimately has to examine and sign off on this chart review.

Also, Classen et al, like previous investigators, did not really try to distinguish preventable from unpreventable adverse events:

We used the following definition for harm: “unintended physical injury resulting from or contributed to by medical care that requires additional monitoring, treatment, or hospitalization, or that results in death.” Because of prior work with Trigger Tools and the belief that ultimately all adverse events may be preventable, we did not attempt to evaluate the preventability or ameliorability (whether harm could have been reduced if a different approach had been taken) of these adverse events. All events found were classified using an adaptation of the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention’s Index for Categorizing Errors.

There’s the problem right there. Not all adverse events are preventable. We can argue day and night about what percentage of adverse events are potentially preventable; there are sincere disagreements based on evidence on how to determine that number. The problem comes when adverse events are automatically equated with medical errors. The two are not the same. To be fair, Classen et al try not to do this. The authors are very up front that they deem 100% of the adverse events they detected to be potentially preventable. In any case, Classen et al found in 795 hospital admissions in three hospitals and adverse event rate of 33.2% and a lethal adverse event rate of 1.1%, or 9 deaths.

Again, in fairness, I note that Classen et al never extrapolate their numbers to all hospital admissions. Nor did their study differentiate inpatient adverse events or death as due to medical errors (and therefore preventable) or unpreventable. Rather, the purpose of their study was to demonstrate how traditional methods of reporting underestimate adverse events and how the Global Trigger Tool is far more sensitive at detecting such events than voluntary reporting methods. They showed that. None of that stopped Makary and Daniel from taking this one study of less than 1,000 hospital admissions and extrapolating it to 400,000 preventable deaths in hospitals per year. That is the peril from extrapolating from such small numbers.

Landrigan et al: Not as high as Classen, but still too high and not improving

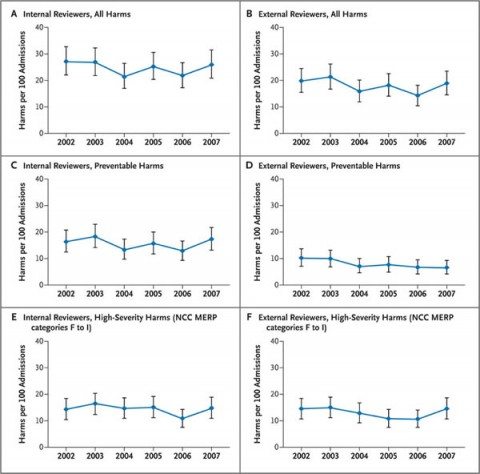

Another study examining the use of the Global Triggering Tool was carried out by Landrigan et al in 10 North Carolina hospitals and published in the NEJM in 2010. I mention it precisely because it uses similar methods to the ones used by Classen et al and comes up with dramatically lower numbers of preventable deaths. It is also a useful study because it examines temporal trends in estimates of harm, asking the question, “Have statewide rates of harm been decreasing over time in North Carolina?” In brief, examining 2,341 hospital admissions over the ten North Carolina hospitals chosen and using internal and external reviewers to judge whether adverse events detected were preventable, Landrigan et al found that there was a reduction in preventable harms identified by external reviewers that did not quite reach statistical significance (P=0.06), with no significant change in the overall rate of harms. This is a depressing finding, although one wonders if the finding might have reached statistical significance if more hospitals had been included.

Overall, despite the lower percentages, the findings of Landrigan et al are not dissimilar to those of Classen et al taking into account that Landrigan et al deemed 63.1% of the adverse events that they identified as preventable, as opposed to the 100% that Classen et al chose. In their 2,341 hospital admissions, Landrigan et al found an adverse event rate of 18.1%, a lethal adverse event rate of 0.6%, and deemed 14 deaths to have been preventable, with the data summarized in a graph below:

I also note that, like Classen et al, Landrigan et al made no effort to extrapolate their findings to the whole of the United States. That was not the purpose of their study. Rather, the purpose of their study was to ask whether rates of adverse events were declining in North Carolina hospitals from 2002 to 2007. None of that stopped Makary and Daniel from extrapolating from Landrigan’s data to close to 135,000 preventable deaths.

HealthGrade’s failing grade

By far the largest study cited by Makary and Daniel is the HealthGrades Quality Study. The HealthGrades study has the advantage of having analyzed patient outcome data for nearly every hospital in the US using data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. Indeed, 37 million Medicare discharges from 2000-2002 were examined using AHRQ’s PSI (Patient Safety Indicator) Version 2.1, Revision 1, March 2004 software application. The authors identified the rates of 16 patient safety incidents relevant to the Medicare population. Four key findings included:

- Approximately 1.14 million total patient safety incidents occurred among the 37 million hospitalizations in the Medicare population from 2000 through 2002.

- The PSIs with the highest incident rates per 1,000 hospitalizations at risk were Failure to Rescue, Decubitus Ulcer, and Post-operative Sepsis. These three patient safety incidents accounted for almost 60% of all patient safety incidents among Medicare patients hospitalized from 2000 through 2002.

- Of the total of 323,993 deaths among patients who experienced one or more PSIs from 2000 through 2002, 263,864, or 81%, of these deaths were potentially attributable to the patient safety incident(s).

- Failure to Rescue (i.e., failure to diagnose and treat in time) and Death in Low Mortality Diagnostic Related Groups (i.e., unexpected death in a low risk hospitalization) accounted for almost 75% of all mortality attributable to patient safety incidents.

One notes that these data were all derived from Medicare recipients, which means that the vast majority of these patients were over 65. Indeed, the authors of the report themselves note that this is so, pointing out that Medicare patients have much higher patient safety incident rates, “particularly for Post-operative Respiratory Failure and Death in Low Mortality DRG where the relative incident rate differences were 85% and 55% higher, respectively, in the Medicare population as compared to all patients.” So just from the fact that this is a study of Medicare recipients, who are much older than non-Medicare recipients, you know that this study is going to skew towards sicker patients and a higher rate of adverse events, even if the care they received was completely free from error. Still, that didn’t stop Makary and Daniels from including this study and estimating 251,000 potentially preventable hospital deaths per year.

Sloppy language, sloppy thinking

No one, least of all I, denies that medical errors and potentially substandard care (again, the two are not the same thing, although there is overlap) are a major problem. If I didn’t believe that, I wouldn’t have devoted so much of my time over the last three years to quality improvement in breast cancer care, and, as I’ve noted before, I’ve frequently been surprised at the variability in utilization of various treatments among hospitals just in my state.

I’ll paraphrase what the IOM said in its 1999 report: You cannot improve what you cannot measure. The problem that we have here is that everybody seems to be using different language and terms about what we are measuring. For example, Makary and Daniels argue:

Human error is inevitable. Although we cannot eliminate human error, we can better measure the problem to design safer systems mitigating its frequency, visibility, and consequences. Strategies to reduce death from medical care should include three steps: making errors more visible when they occur so their effects can be intercepted; having remedies at hand to rescue patients; and making errors less frequent by following principles that take human limitations into account (fig 2⇓). This multitier approach necessitates guidance from reliable data.

It’s hard to disagree with this. Who can argue with the need for reliable data upon which to base our recommendations and efforts to improve quality of care? However, the devil, as they say, is always in the details. Language matters, as well. Adverse events happen even in the absence of medical errors. Many adverse events are not preventable and do not imply medical errors or substandard medical care. Moreover, determining whether a given medical error directly caused or contributed to a given death in the hospital is far from straightforward in most cases. That’s why I don’t like the term “medical errors” in the context of this discussion, except in egregious cases, particularly as it is often used in the lay press, to imply that any potentially preventable death must have been due to an error. Makary and Daniels fall into that trap in perhaps the most quoted part of their BMJ article:

There are several possible strategies to estimate accurate national statistics for death due to medical error. Instead of simply requiring cause of death, death certificates could contain an extra field asking whether a preventable complication stemming from the patient’s medical care contributed to the death. An early experience asking physicians to comment on the potential preventability of inpatient deaths immediately after they occurred resulted in an 89% response rate. Another strategy would be for hospitals to carry out a rapid and efficient independent investigation into deaths to determine the potential contribution of error. A root cause analysis approach would enable local learning while using medicolegal protections to maintain anonymity. Standardized data collection and reporting processes are needed to build up an accurate national picture of the problem. Measuring the consequences of medical care on patient outcomes is an important prerequisite to creating a culture of learning from our mistakes, thereby advancing the science of safety and moving us closer towards the Institute of Medicine’s goal of creating learning health systems.

Note in the first sentence they refer to “death due to medical error,” while in the second sentence they propose asking whether a “preventable complication stemming from the patient’s medical care contributed to the death.” This basically conflates potentially preventable adverse events and deaths with medical errors, when the two are not the same. Rather, I (and many other investigators) prefer to divide such deaths into preventable and unpreventable. Unpreventable deaths include deaths that no intervention could have prevented, such as death from terminal cancer. Preventable deaths include, yes, deaths from medical error, but they also include deaths that, for example, might have been prevented if patient deterioration was picked up sooner. Whether not picking up such deterioration is an “error” or the result of a problem in the system might or might not be clear. Unfortunately, conflating the two, deaths due to medical error and potentially preventable deaths, only provide ammunition to quacks like the one currently engaged in a campaign against me.

How much death is due to medical error, anyway?

I’ll conclude by giving my answer to the question that all of these studies ask, starting with the IOM report: How many deaths in the US are due to medical errors? The answer is: I don’t know! And neither do Makary and Daniels—or anyone else for sure. I do know that there might be a couple of hundred thousand possibly preventable deaths in hospitals, but that number might be much lower or higher depending on how you define “preventable.” I’m also pretty sure that medical errors, in and of themselves, are not the number three cause of deaths. That’s because medical errors rarely occur in isolation from serious medical conditions, which means it’s very to attribute most deaths to primarily a medical error. That number of 250,000 almost certainly includes a lot of deaths that were not primarily due to medical error, given that that’s 9% of all deaths every year.

But it’s even more than that. Whenever you see an estimate of how many deaths are “deaths by medicine,” it’s very helpful to compare that estimate with what we know to assess its plausibility. As I mentioned above, According to the CDC, of the 2.6 million deaths that occur every year in the U.S., 715,000 occur in hospitals, which means that, if Makary’s estimates are correct, 35% of all hospital deaths are due to medical errors. But the plausibility of Makary’s estimate is worse than that. Remember that the upper estimate used by Makary and Daniels is 400,000 inpatient deaths due to medical error. That’s 56%—yes, 56%—of all inpatient deaths? Seriously? It’s just not anywhere near plausible that one-third to over one-half of all inpatient deaths in the US are due to medical error. It just isn’t.

Here are some other things I know. I know that the risk of death and complications is a fairly meaningless number unless weighed against the benefits of medical care, a point that Harriet Hall made long ago, noting for example that an “an insulin reaction counts as an adverse drug reaction, but if the patient weren’t taking insulin he probably wouldn’t be alive to have a reaction.” I also know that Makary’s suggestion that there should be a field on death certificates asking whether a problem or error related to patient care contributed to a patient’s death will be a non-starter in the litigious United States of America, promises of anonymity notwithstanding.

Over the last three years, I’ve learned for myself from firsthand experience just how difficult it is to improve the quality of patient care. I’ve also learned from firsthand experience that nowhere near all adverse outcomes are due to negligence or error on the part of physicians and nurses. None of this is to say that every effort shouldn’t be made to improve patient safety. Absolutely that should be a top health care policy priority. It’s an effort that will require the rigorous application of science-based medicine on top of expenditures to make changes in the health care system, as well as agreement on exactly how to define and measure medical errors. After all, one death due to medical error is too much, and even if the number is “only” 20,000 that is still too high and needs urgent attention to be brought down. Unfortunately, I also know that, human systems being what they are, the rate will never be reduced to zero. That shouldn’t stop us from trying to make that number as close to zero as we can.

ADDENDUM: Here’s a great video that makes similar arguments.