SBM frequently receives questions from readers asking for more information or even challenging our position on various topics. We make extensive efforts to answer such questions, since engaging with the public is one of the primary purposes of this blog. In fact, I specifically chose the blog format because of its interactive nature and the ability to rapidly respond to items in the news or being discussed publicly.

SBM frequently receives questions from readers asking for more information or even challenging our position on various topics. We make extensive efforts to answer such questions, since engaging with the public is one of the primary purposes of this blog. In fact, I specifically chose the blog format because of its interactive nature and the ability to rapidly respond to items in the news or being discussed publicly.

Sometimes it’s helpful to provide answers to questions in the form of its own post. I do this when the questions are common or explore some new or interesting angle of a topic. I am also more likely to engage when the questions are polite and genuine.

We recently received the following e-mail which meets all these criteria, so here is my response. I will reprint the e-mail in sections as I address each question.

Organic pesticides

I have the utmost respect for the scientific method, and we subscribe to the Skeptical Inquirer. I respect much of what your organization does, and I do not believe that Reiki or Therapeutic Touch is effective, unless the person receiving these therapies believe they work. However, your organization seems to go out of its way to disprove things like the benefit of organic produce which has less pesticides than conventional produce. You claim that natural pesticides could be just as harmful. Here are some examples of these natural pesticides: apply 1 tablespoon of canola oil and a few drops of ivory soap to the leaves of plants and vegetables to repel insects. Also, apply 2 TBSPS of hot pepper sauce with a few drops of ivory soap to leaves, use baking soda and water or pureed onions to repel insects. How can you claim that these innocuous substances are as harmful as conventional pesticides?

The e-mailer is mischaracterizing our position, setting up a straw man. We never specifically mentioned the “natural” pesticides she lists above, and so never claimed they were harmful. I have written about this topic several times myself and here are the conclusions I have drawn from the evidence.

In 2012 I reported on a systematic review of studies of the health effects of organic produce, stating:

The recent review did find that organic produce had fewer pesticide residues than conventional farming. However, there is no evidence that these low levels of pesticides present any health risk.

But in a 2010 SBM article I pointed out:

With regard to pesticides, it must also be noted that organic farming, while using methods to minimize pests and the need for pesticides, still uses organic, rather than synthetic, pesticides. For example a rotenone-pyrethrin mixture is commonly used. Such pesticides are not as well studied as synthetic pesticides, often require more applications, and may persist longer in the soil. In fact the use of “natural” pesticides is nothing more than an appeal to the naturalistic fallacy – there really is no evidence for superior safety, and they have not been adequately studied.

To summarize, there is no evidence that organic produce is more healthful or less risky than conventional produce. There is some evidence for increased synthetic pesticide residue on conventional produce, but such reside is still well below safety limits. These studies, however, are rigged because they don’t measure organic pesticide residues. This includes many untested and potentially-harmful agents that generally have to be used more often and in larger amounts than synthetic pesticides. It is assumed that organic pesticides are harmless because they are “natural,” but this is a fallacy.

When they are studied it is found that some natural pesticides can have the same potential for adverse health and environmental effects as synthetic ones.

Of course, there is a wide range of practices under the banner of “organic.” Not all organic farmers use natural pesticides. There are non-chemical approaches such as using predator species and careful crop selection. I never claimed that all organic farmers use natural pesticides, just that some do because they are allowed to.

The bottom line remains – pesticide residues in conventional farming are below safety limits and there is no evidence that they cause any adverse health effect at those levels. Meanwhile, some organic farmers use natural pesticides with the false security that they are “natural” when in fact they are likely no different in safety from synthetic pesticides and often need to be used in larger amounts.

I would also point out that while exploring non-chemical approaches to pest management is a great idea, and may even be practical for small farms, there is currently no way we can produce food for 7 billion people without pesticides.

Oil-based pesticides, for example, may be a great option for a home garden or small farm, but they generally need to be sprayed directly on insects to have an effect, and have little ongoing effect. Frequent applications are therefore necessary.

Acupuncture

The e-mailer continues:

On another matter, your organization claims acupuncture is nothing more than woo. Of course there is no proof that qi exists, but there are western explanations such as increased blood flow or the involvement of neurotransmitters which could explain why acupuncture may work in limited situations. One example is the use of acupuncture to help alleviate the nausea and vomiting from chemotherapy. Do you believe the American Medical Association is a woo organization? The AMA has stated that indeed, acupuncture can help patients who experience nausea from chemotherapy. I have read the research which is very convincing because they use control groups.And there is more than one study.

There are two points being made here, both extremely common: there are respectable medical organizations who endorse acupuncture as effective, and aren’t there plausible science-based mechanisms for acupuncture?

Generally speaking, if multiple scientific and professional organizations systematically review the evidence addressing a specific question and arrive at position statements that generally agree with each other, then it is reasonable to take such positions seriously. Unfortunately, in the case of acupuncture such organizations sometimes have not systematically reviewed the evidence, but have simply allowed acupuncturists to provide position statements based upon their own dogma.

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) 1996 position statement on acupuncture is probably the best example. This is still presented as evidence for mainstream acceptance of acupuncture. I did a thorough analysis here, but the short version is that the authors of the statement were all acupuncturists who made statements that were in direct conflict with the published evidence.

In the case of the AMA they did apparently review the evidence, but their vague statements are being misrepresented as more positive than they are. Here, I believe, is the AMA position referenced by the e-mailer – actually a consensus statement published in JAMA from 1998. They concluded:

Acupuncture as a therapeutic intervention is widely practiced in the United States. Although there have been many studies of its potential usefulness, many of these studies provide equivocal results because of design, sample size, and other factors. The issue is further complicated by inherent difficulties in the use of appropriate controls, such as placebos and sham acupuncture groups. However, promising results have emerged, for example, showing efficacy of acupuncture in adult postoperative and chemotherapy nausea and vomiting and in postoperative dental pain.

This is a long way away from saying that acupuncture works for nausea. Most “promising results” do not hold up to well-designed clinical trials.

In reviewing the current research looking at acupuncture and chemotherapy induced or post-operative nausea and vomiting, I find that it is plagued by the same problems with the acupuncture literature in general. Most studies are not controlled with sham or placebo acupuncture. Most that are controlled do not report allocation blinding – there is a particular problem in acupuncture studies with subjects becoming unblinded to their treatment group. Also, reviews are contaminated with “electroacupuncture” studies, which introduce the new variable of electrical stimulation.

There is also the problem that the evidence strongly shows an almost-completely-positive bias in the Asian literature on acupuncture. Any reviews containing studies from China, for example, are therefore suspect.

Those few studies that are best controlled tend to be negative. For example, a 2015 study of stimulation at the K1 point in chemotherapy induced nausea, with a sham acupuncture control, showed no benefit.

A 2006 Cochrane systematic review concluded:

This review complements data on post-operative nausea and vomiting suggesting a biologic effect of acupuncture-point stimulation. Electroacupuncture has demonstrated benefit for chemotherapy-induced acute vomiting, but studies combining electroacupuncture with state-of-the-art antiemetics and in patients with refractory symptoms are needed to determine clinical relevance. Self-administered acupressure appears to have a protective effect for acute nausea and can readily be taught to patients though studies did not involve placebo control. Noninvasive electrostimulation appears unlikely to have a clinically relevant impact when patients are given state-of-the-art pharmacologic antiemetic therapy.

These are curiously mixed results. Often treatment reduced vomiting but not nausea, or reduced acute but not delayed symptoms. Most were not adequately controlled, with properly blinded sham groups.

While I agree that the studies for acupuncture are more consistently positive with nausea and vomiting than other indications, the research methods are still wanting, contain significant limitations, and overall are unimpressive. It is possible that there is simply a larger placebo effect for nausea and vomiting than other tested symptoms. It is also possible that local pain does have a temporary inhibitory effect on vomiting, but I don’t think the literature is sufficient to confidently conclude this.

None of this, however, leads to the conclusion that “acupuncture works.” This blends into the other point about mechanism of action.

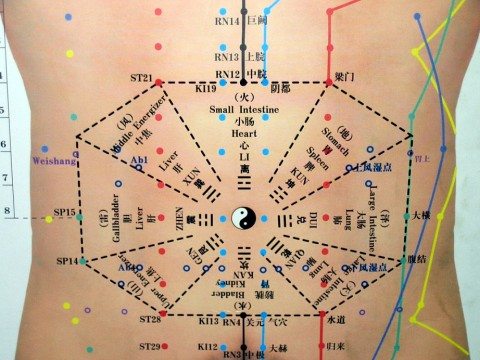

What is clear from the scientific literature is that chi does not exist. It is a pre-scientific delusion. It is also clear the acupuncture points do not exist – they have no basis in reality, and adhering to acupuncture points has no clinical effect. It is also clear that specific acupuncture techniques, such as inserting needles to a specific depth, and eliciting a “de qi”, also have no effects.

What, then, is acupuncture? Give me a definition that does not involve sticking needles into acupuncture points. If you count any local application of pressure, minor tissue trauma, or pain with electricity, needles, dull toothpicks, heat, or whatever as “acupuncture” then the definition loses any specific scientific meaning.

It is possible, for example, that any physical stimulation might contain a modest and short-lived effect to reduce the perception of pain or nausea. What the studies show is that this non-specific effect is minor to non-existent, and is swamped by other non-specific effects such as simply being nice to patients.

As a scientific hypothesis, acupuncture has failed. It is based on no unique understanding of anatomy or physiology and entails no specific effects. Acupuncture training is without benefit, as poking people randomly with toothpicks after a 10-minute prep seems to be just as effective. We need to completely dispense with any notion of chi or acupuncture points.

The fact that stuff happens in the local tissue after needle insertion does not mean that this stuff (any physiological changes) is a “mechanism for acupuncture.” That conclusion is highly misleading, for the reasons stated above.

Perhaps in the end we will demonstrate that rubbing parts of the body may be a benign and effective way of distracting people from their pain or nausea, or just giving them something to do, or may provide some counter-irritation (like rubbing your elbow after banging it into something). Tactile stimulation may even inhibit the vomiting reflex. None of this, however, is acupuncture.

These distinctions are important. Scientific questions need to be clear and unambiguous, as do definitions. Proponents of the worst manifestations of “medical acupuncture” exploit the slippery definition of acupuncture often employed to argue that these dubious, transient, and minor nonspecific effects show that “acupuncture works” and therefore justify using “acupuncture” to treat real medical conditions.

Supplements

She raises one more issue:

When it comes to herbal supplements, many are indeed unsafe, and possibly contaminated. However, ConsumerLab does test many herbs for purity. I suffer from osteoarthritis, and take several herbs which have helped me. Sometimes the evidence is only anecdotal, but often that’s because there is little money to be had by testing these non- drug supplements.

I can’t really repeat the many posts we have here on supplements, which collectively address her questions. Let me just highlight a few points.

While some supplements are tested and some do have reasonable purity, on the whole the industry is poorly regulated, and rife with contamination, product substitution, and dose variability. Many are adulterated with prescription drugs. The fact that they are not universally contaminated is of little comfort.

We also point out that effective herbs are drugs and should be treated as such. In addition to the above problems, they are unpurified, and may contain variable doses of many active ingredients. Herbs are dirty, variable, and poorly-regulated drugs.

Most of the popular herbs on the market also do not work for the indications for which they are marketed, or they lack sufficient evidence to know their efficacy.

It also cannot be assumed that they are safe – they often have the same toxic effects and drug interactions as other drugs.

These concerns should not be brushed aside. Nor is it legitimate to defend anecdotal evidence by saying there is little money for testing. This is both untrue and irrelevant. Anecdotal evidence is completely inadequate, whether or not there is funding for well-controlled trials.

But further – the supplement industry is largely the same as the pharmaceutical industry. Big Pharma and Big Supplement are often the same companies. They have plenty of money to conduct research. Supplements are also a billion-dollar industry.

The NIH has also granted millions of dollars for supplement research, and has funded many high-quality studies.

The problem is not that there is no money for research. The problem is there is no regulatory incentive for research. Further, there has been research (mostly publicly or academically funded) but it is mostly negative. Herbs that have active ingredients that are safe and effective are researched and developed into pharmaceuticals.

Chondroitin and glucosamine for arthritis, for example, have been extensively studied. A 2009 review found:

In the literature satisfying our inclusion criteria, glucosamine sulfate, glucosamine hydrochloride, and chondroitin sulfate have individually shown inconsistent efficacy in decreasing OA pain and improving joint function.

A large 2 year study published in 2010 found:

Over 2 years, no treatment achieved a clinically important difference in WOMAC pain or function as compared with placebo.

Also keep in mind that we have no bias or ideological axe to grind against glucosamine or chondroitin for arthritis, or any particular herbal product. We are simply reporting the findings of the research and putting it into a meaningful clinical and regulatory context.

Conclusion: The rules of science must apply everywhere

It is also worth pointing out that science-based medicine in general is about raising the bar of scientific evidence before concluding that any treatment is safe and effective. There are numerous challenges to doing reliable clinical research, and the literature is filled with bias and error.

We apply these standards universally, but it is easy to feel picked on when we apply them to some treatment in which you believe. The e-mailer goes on to say that she agrees with us when we criticize homeopathy or anti-GMO nonsense. Well, we are using the same process when we analyze the claims made for organic produce, acupuncture, and supplements.