Last week, I wrote a magnum opus of a movie review of a movie about a physician and “researcher” named Stanislaw Burzynski, MD, PhD, founder of the Burzynski Clinic and Burzynski Research Institute in Houston. I refer you to my original post for details, but in brief Dr. Burzynski claimed in the 1970s to have made a major breakthrough in cancer therapy through his discovery of anticancer substances in the urine that he dubbed “antineoplastons,” which turned out to be mainly modified amino acids and peptides. Since the late 1970s, when he founded his clinic, Dr. Burzynski has been using antineoplastons to treat cancer. Over the last 25 years or so, he has opened a large number of phase I and phase II clinical trials with little or nothing to show for it in terms of convincing evidence of efficacy. Worse, as has been noted in a number of places, high doses of antineoplastons as sodium salts are required, doses so high that severe hypernatremia is a concern.

Although antineoplastons are the dubious cancer therapy upon which Dr. Burzynski built his fame, they aren’t the only thing he does. Despite the promotion of the Burzynski Clinic as using “nontoxic” therapies that “aren’t chemotherapy” by “natural medicine” cranks such as Joe Mercola and Mike Adams, Dr. Burzynski’s dirty little secrets, at least as far as the “alternative medicine” crowd goes, are that (1) despite all of the attempts of Dr. Burzynski and supporters to portray them otherwise antineoplastons are chemotherapy and (2) Dr. Burzynski uses a lot of conventional chemotherapy. In fact, from my perspective, it appears to me as though over the last few years Dr. Burzynski has pivoted. No longer are antineoplastons the center of attention at his clinic. Rather, these days, he appears to be selling something that he calls “personalized gene-targeted cancer therapy.” In fact, it’s right there in the first bullet point on his clinic’s webpage, underlined, even! Antineoplastons aren’t even listed until the third bullet point.

But what is “personalized gene-targeted cancer therapy,” according to Dr. Burzynski? Here is how it is described:

Our approach to cancer is a result of Dr. Burzynski’s extensive experience in cancer research in the field of genetics and genomics.

Personalized Treatments offered by the Burzynski Clinic are individual treatment plans, customized for each patient, based on:

- Identification of oncogenes responsible for the growth of cancerous cells in individual patients

- Selection of targeted pharmaceuticals that selectively kill cancer cells carrying the identified abnormal genes

The main goal of a Personalized Treatment is to match the right patient to the right treatment to achieve maximum effectiveness with minimum side effects.

Elsewhere, Dr. Burzynski claims:

In some cases conventional therapy is the most appropriate treatment for a patient. Our Clinic offers customized combination therapies consisting of conventional therapy and other approved targeted therapies to maximize effectiveness while minimizing the side effects that typically occur when using the traditional therapies alone.

And:

There are currently close to 30 targeted therapeutics approved by the FDA (as of January 2011). This number grows rapidly with the advancement of the research in genomics. All of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved gene-targeted medications are available for treatment at the Burzynski Clinic. The combination of targeted medications is customized for each patient and determined by the type of oncogenes involved in patient’s cancer (Personalized Treatment).

Dr. Burzynski is also not shy about being interviewed by promoters of alternative medicine, such as Mike Adams. For example, here are a typical radio interview (on Oprah Radio, of course!) and videos like this one:

And this one:

Note that the first few minutes of the second video are spent portraying Dr. Burzynski as a “brave maverick doctor” and pioneer being oppressed, suppressed, and persecuted by The Man, combined with Dr. Burzynski calling the FDA and NCI “criminal” and using every “health freedom” argument in the book. Antineoplastons are portrayed as a cancer cure that causes brain tumors to “vanish in many children.” Finally, around the 4:30 mark, we see Dr. Gregory Burzynski, Dr. Burzynski’s son, talking about genomic profiling of cancers and biomarkers in the blood and in circulating tumor cells. If this segment weren’t embedded in a bunch of paranoid conspiracy mongering about big pharma, the FDA, and the NCI, plus a claim that surgery will no longer be necessary for cancer, what’s left over doesn’t sound too different from what quite a few “conventional” cancer researchers say about “personalized medicine.” Well, that and what Dr. Burzynski says about tumor suppressors. He seems to think that all tumor suppressors prevent mutations, which is, of course, not true. Some of them do other things. Be that as it may, the claim made in the video is that, with a combination of antineoplastons and “personalized therapy,” Dr. Burzynski can cure many cancer patients with stage IV disease. But how credible is this claim? What, exactly, is he doing? It’s hard to figure out from his website, but looking elsewhere can provide hints. In the meantime, let’s start with a description of what “personalized medicine” means to cutting edge cancer researchers.

“Personalized cancer treatment” in science-based medicine

At the risk of annoying some colleagues I know, I’m going to point out that I never really liked the term “personalized cancer therapy” or its many variants, for the simple reason that it always struck me as more of a marketing term than a scientifically meaningful description of what targeting therapy to the genetic makeup of a patient’s tumor will eventually entail. In fact, I think I now prefer another term, which has been used by Cancer Research U.K., namely “stratified medicine.” The reason is that what we as clinicians are doing when we “personalize” or “individualize” therapies isn’t really “personalizing” the therapy so much as using various measurements and biomarkers to place patients into groups of patients who respond to specific therapies. What the modern version of “personalized” therapy is really doing is producing more and more groups of patients, each of which, is smaller than the last, to be matched to more and more therapies. Whether the groups will eventually reach an N of 1, I don’t know, but that is the goal. Only then will we truly have “personalized medicine.”

My personal irritation at the proliferation of certain terms notwithstanding, I actually do believe that the stratification and matching of patients with therapies based on genomics, proteomics, and biomarkers is the future of cancer treatment, and, to some extent, the future is now. However, “personalized” medicine is in its infancy, as I have pointed out in previous posts on the topic, Hope and hype in genomics and “personalized medicine” and Integrating patient experience into research and clinical medicine: Towards true “personalized medicine.” True, we do have several targeted therapies that inhibit or target a single important molecule. For instance, in breast cancer, Herceptin (trastuzumab) targets the HER2 oncogene, which is amplified in some breast cancers. Another example, Gleevec (imatinib mesylate), inhibits the tyrosine kinase activity of the bcr-abl oncogene product as well as receptor tyrosine kinases encoded by the c-kit and platelet-derived growth factor receptor oncogenes and is very effective against tumors that make too much of one these oncogenes, such as gastrointestinal stromal tumor and Philadelphia-positive (Ph+) hematological malignancies such as chronic myelogenous leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Now, there are numerous other examples, so many that they are listed on the NCI website.

In fact, the idea of targeted therapy in cancer is not new. In fact, as I learned while writing my current grant, arguably the concept dates back over 100 years. Indeed, the very concept of targeted therapy was first applied to breast cancer when oophorectomy (removal of the ovaries) was first proposed as a therapy by Albert Schinzinger in 1889 and then George Thomas Beatson reported seven years later that oophorectomy could bring about complete remissions in young women with inoperable or locally recurrent breast cancer. Decades would pass before the development of the selective estrogen modulator, Tamoxifen, and it would be still more decades before aromatase inhibitors. Moreover, using biomarkers to follow cancer and to predict response to treatment is nothing new either. For example, it’s long been known that the presence of the estrogen receptor (ER) in breast cancer implies that treatment with antiestrogen drugs like Tamoxifen is likely to result in a a response and that lack of ER in a tumor means that Tamoxifen won’t work. Similarly, we’ve used prostate-specific antigen (PSA) as a biomarker for prostate cancer and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) as a biomarker for colon cancer for decades. The difference between the way drugs were targeted to cancers a couple of decades ago and now is the explosion of genomics knowledge that has occurred over the last decade. As I’ve pointed out, we are now producing terrabytes and petabytes of genomic data about cancers, a flood of information that we have only relatively recently started seriously developing the tools needed to analyze and disciplines (systems biology, bioinformatics, genomics, etc.) to organize and determine how best to translate it into therapies. We even use one such test in breast cancer, the Oncotype DX, assay, which has allowed oncologists to identify patients who can safely skip adjuvant chemotherapy, but it is a relatively simple test, consisting of only 21 genes, and its results are not always clear-cut.

What we are learning, as I have lightheartedly appropriated Douglas Adams’ masterwork to say before, is that cancer is complicated. You just won’t believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly complicated it is. I mean, you may think it’s complicated to understand basic cell biology, but that’s just peanuts to cancer. All you have to do is to look at the genetic derangements in typical prostate cancers to get a flavor for how daunting the task of developing personalized treatments of cancer will be, much less curing it. Think of it this way. The examples of genomic derangements in a few prostate cancers were incredible, and there are different sets of genomic derangements that vary by cancer type, of which there are hundreds. Add to that the fact that, as Dr. Burzynski himself emphasizes, cancers are heterogeneous, with different genetic derangements in different parts of the tumor, and you get a flavor of how difficult “personalizing” cancer therapy based on its genomic makeup and biomarkers will be. It will take an incredible amount of research, both basic and clinical, in order to learn the best ways to match the genomic makeup of patient tumors to the most effective targeted therapies. As a commentary by James H. Doroshow last year noted, even leaving aside the practical obstacles (FDA approval, access to fresh tissue, and the like) at least one huge obstacle remains:

Finally, if these obstacles are surmounted, widespread adoption of a predictive therapeutic biomarker assumes, as a matter of course, that the assay(s) for the biomarker in question is fit for its scientific purpose, and that our understanding of the molecular pathways to be investigated justifies the specific use of a particular portfolio of gene expression or mutational analyses, for example, and these are anything but trivial assumptions.

And there’s the problem. Burzynski’s approach to “personalized gene-targeted anticancer therapy” appears to fall prey to the assumption that the assays used are fit for the scientific purpose for which he is using them and, even worse, that he knows enough about the molecular pathways to be investigated to reliably use the results of such assays to guide anticancer treatment. In essence, it’s as though Dr. Burzynski read a book called Personalized Cancer Therapy for Dummies and decided he is an expert in genomics-based tailoring of targeted therapies to individual cancer patients. I’ll try to show you what I mean.

What Burzysnki claims he can do with “personalized gene-targeted therapy”

In order to determine what it is that the Burzynski Clinic is doing that it calls “personalized gene-targeted cancer therapy,” I started searching around the web. I also had a brief e-mail correspondence with Renée Trimble, Director of Public Relations for the Burzynski Institute. She’s the one who, in the wake of Marc Stephens’ harassment of bloggers, sent out a press release apologizing for his behavior while at the same time basically saying that the Burzynski Clinic would keep using the legal system to try to silence bloggers who criticize it. However, she was polite with me, probably because of the positions I hold at an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center. Mostly, her information was only marginally more helpful than what I could find on the Burzynski Clinic website and around the Internet, but she did confirm at least one fact that needed confirming. Then, there is also this video, produced by the Burzynski clinic itself:

What interested me about this video, ironically enough, is how bland and unremarkable a lot of it was. Clearly, the producer went to great lengths to make Burzynski’s lab look like any other molecular and cell biology lab—even like my lab. The other thing that interested me was how the video emphasizes the use of FDA-approved medications. Finally, there was a clue (to me, at least) about what it is that Burzynski is doing. At around the three minute mark, the announcer states:

We combine gene-targeting drugs and low dose chemo, if needed.

Then a very sharply-dressed man named Azad Rastegar appears and says:

The way we look at cancer here at the Burzynski Clinic is that it’s more than just the tumor site. Obviously, that’s very important and significant for figuring out how to address the cancer in the patient, but what we want to do is to identify the genes that are involved in that particular patient’s cancer. With that, then we can start creating more customized and personalized treatment plans that involve gene-targeted medications targeting, obviously, the genes involved in that patient’s cancer. This way we’re able to reduce side effects. We’re able to reduce any time-wasting on ineffective drugs and cater it, obviously, much more to the patients and their individual cancer needs.

It all sounds so reasonable, and, indeed, this is exactly the sort of thing that lots of cancer centers are trying to do. But how this sort of approach is implemented makes all the difference in the world, and the question I had was whether Dr. Burzynski is taking anything resembling the right sort of approach to this problem. From the description above, it sounded very much to me as though Dr. Burzynski is combining various targeted agents with metronomic chemotherapy. I know a thing or two about metronomic chemotherapy, because I was involved in a project whose end result was to be the testing of metronomic chemotherapy against cancer and because the concept is a spinoff of the work of one of my scientific heros, the late Judah Folkman. Basically, metronomic chemotherapy is an approach to chemotherapy that uses repetitive, low doses of chemotherapy drugs (or even continuous infusions of low dose chemotherapy) designed to minimize toxicity and target the tumor blood vessels rather than targeting the tumor cells themselves. The concept behind this strategy is that blood vessels are lined by genetically stable endothelial cells, they do not evolve resistance, and chemotherapy can be antiangiogenic. The drawback to metronomic chemotherapy is that long periods of therapy may be required and the cumulative doses of chemotherapy may end up being actually higher than more standard therapies. On the other hand, this latter aspect may not be a drawback because metronomic chemotherapy may allow a greater cumulative dose, with a concurrent greater cumulative effect. As I wrote before the last time I discussed metronomic chemotherapy, it’s a promising concept, but thus far clinical trials in humans can only be characterized as fairly disappointing.

Whether this is what Dr. Burzynski is doing or not with the chemotherapy part of his approach, I don’t know for sure, but it sure sounds like it. For example, in Knockout: Interviews With Doctors Who Are Curing Cancer and How to Prevent Getting It in the First Place by Suzanne Somers, Dr. Burzynski is interviewed and, ironically, reveals a great deal (to me, at least) about what he is doing. For example:

For the majority of Dr. Burzynski’s patients he does not use any chemotherapy, but for some patients the chemotherapy is used in lower dosages, which are below the threshold of significant side effects. Dr. Burzynski takes advantage of the synergistic effect of such combinations…

Except that he doesn’t demonstrate that these combinations are synergistic in preclinical studies or clinical trials before prescribing them off-label.

Later in the interview, Somers (SS) asks Dr. Burzynski (SB) about breast cancer, and he replies:

SB: At the moment we use a different approach. We study which genes in individual patients are abnormal, trying to determine the genetic signature of cancer in these patients. With our methods, we can have answers for the patient in about three days based on blood tests. Once we identify the most important oncogenes involved in cancer for that individual, we select a group of four to six medications from those twenty-four which are now approved by the FDA and use them to hit those genes which are causing the cancer to progress. This is like “boutique treatment” because for every patient we design a treatment plan. When we do this we have a very good chance to have positive results in most patients.

SS: How many respond?

SB: About 85 per cent for whom we have the proper gene signature; about 15 percent do not respond. In our responders many of them have tumors which disappear completely and in others the tumors remain small. The problem is finding the genetic signature because for many of these different genetic signatures we don’t have blood tests…yet.

Note that at the time this book was published, Dr. Burzynski was claiming that he could identify who would benefit from specific targeted therapies simply from blood tests. If he could do this for real, Burzynski could easily publish in high impact journals like Clinical Cancer Research, the Journal of Clinical Oncology, or another high impact clinical cancer journal. Heck, a result like that could probably make it into general medical journals, such as the New England Journal of Medicine or The Lancet, which have an even higher impact factor. If he were able to demonstrate that his method of testing tumors and picking targeted therapy could result in a complete response rate anywhere near 85% for breast cancer, even more so. If, as he claims later in the chapter, Dr. Burzynski has patients with pancreatic cancer and advanced liver cancer whose tumors have disappeared within two months after he began treatment, the same would be true. If, as Burzynski claims, he achieves a 50% complete response rate in advanced brain tumors, again, the same would be true. He doesn’t submit his results to these journals. Why not? No doubt it’s The Man keeping him down.

So what tests does Dr. Burzynski use to determine the cocktail of targeted therapies to use in any given patient, anyway?

I learned from multiple patient blogs (and it was confirmed by Ms. Trimble) that Dr. Burzyski uses a test from a company called Caris Life Sciences. The test appears to be the Caris Target Now™ Molecular Profiling test, and this is how it’s described on the company website:

Caris Life Sciences’™ molecular profiling test, Caris Target Now™, examines the genetic and molecular changes unique to a patient’s tumor so that treatment options may be matched to the tumor’s molecular profile.

Caris Target Now helps patients and their treating physicians create a cancer treatment plan based on the tumor tested. By comparing the tumor’s information with data from published clinical studies by thousands of the world’s leading cancer researchers, Caris can help determine which treatments are likely to be most effective and, just as important, which treatments are likely to be ineffective.

The Caris Target Now test is performed after a cancer diagnosis has been established and the patient has exhausted standard of care therapies or if questions in therapeutic management exist. Using tumor samples obtained from a biopsy, the tumor is examined to identify biomarkers that may have an influence on therapy. Using this information, Caris Target Now provides valuable information on the drugs that will be more likely to produce a positive response. Caris Target Now can be used with any solid cancer such as lung cancer, breast cancer, and prostate cancer.

It’s also noted:

Caris Target Now™ was developed and its performance characteristics were determined by Caris Life Sciences, a medical laboratory CLIA-certified in compliance with the U.S. Clinical Laboratory Amendment Act of 1988 and all relevant U.S. state regulations. It has not been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration.

From my perspective, this test looks perfectly fine as a test used for research and clinical trials, but clearly using it to treat patients with off-label cancer drugs outside of a clinical trial is something that I’d be very, very concerned about. But how does it work? It’s described thusly:

Caris Target Now begins with an immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis. An IHC test measures the level of important proteins in cancer cells providing clues about which therapies are likely to have clinical benefit and then what additional tests should be run.

If there is access to a frozen sample of patient tissue available, Caris Life Sciences™ may also run a gene expression analysis by microarray. The microarray test looks for genes in the tumor that are associated with specific treatment options.

As deemed appropriate based on each patient, Caris will run additional tests. Fluorescent In-Situ Hybridization (FISH) is used to examine gene copy number variation in the tumor. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) or DNA sequencing is used to determine gene mutations in the DNA tumor.

Immunohistochemistry is standard for many cancers. For example, in breast cancer, pretty much every pathology lab does immunohistochemistry (using antibodies to detect specific proteins) for at least two proteins, the estrogen receptor and the HER2 oncogene. Sometimes, depending upon the lab and the clinical situation, pathologists will stain for proliferation markers, like Ki-67, or other receptors such as epidermal growth factor receptor. Not uncommonly, pathologists stain for E-cadherin in order to differentiate between two common types of breast cancer, infiltrating ductal carcinoma versus lobular carcinoma. Similarly, breast cancers are often subjected to FISH in order to determine whether the HER2 oncogene is amplified. In other words, none of this is anything particularly remarkable from a clinical standpoint.

What Caris appears to do that’s different from normal clinical evaluation of a tumor sample is, if fresh frozen tissue is available, the performance of cDNA microarray analysis of the messenger RNA isolated from the tumor tissue. cDNA microarrays are a technology that allows scientists to analyze the level of messenger RNA from every known gene in the genome simultaneously. In actuality, technology has moved on from cDNA microarrays, which these days are so 2005, but they’re still good tools and still used to examine differences of thousands of genes simultaneously, either between tissues or in response to drugs or other interventions. Also, newer technology, such as next generation sequencing (NGS) and RNA-Seq. RNA-Seq, for instance, provides the same information that a cDNA microarray does, plus everything else in the transcriptome, such as microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs. microRNAs, in particular, are being appreciated as very important regulators of gene activity because a single microRNA can often regulate hundreds of genes. RNA-Seq is also unbiased in that cDNA microarrays can only measure genes we know, whereas RNA-Seq can be used for discovery of previously unknown RNAs.

However, these techniques are expensive and not yet as common and practical as cDNA microarrays. That Caris isn’t using the latest technology for the test doesn’t mean it might not be potentially worthwhile; after all, a cDNA microarray will detect the levels of all known oncogenes. Caris also apparently does some mutational analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), a test designed to measure gene copy number and thus detect amplified genes. The result is a report like this example report that Caris Life Sciences has posted on one of its websites. The problem, of course, is what a clinician should do with the results. That’s why I say that such a test should probably, except in rare circumstances, only be used for research purposes. Besides, much of what I see isn’t that helpful anyway. For example, if you look at the report, the first agents listed are anthracyclines, such as doxorubicin, because topoisomerase-2A is elevated and taxanes, such as paclitaxel, because TLE3 is elevated. These are basically “Well, duh!” suggestions, because doxorubicin and paclitaxel are normally standard-of-care chemotherapeutic agents for triple negative breast cancer anyway! Particularly useless is the mention that “Lack of HER2 amplification has been associated with lack of benefit from HER2-targeted antibody.” No kidding, given that trastuzumab was designed to treat HER2-positive breast cancer and that clinical samples are routinely checked for HER2 amplification as part of the standard-of-care!

As for the other recommendations, the gene associations listed, many of them are based on associations with response to specific therapies in other tumor types, such as irinotecan in ovarian cancer and cisplatin in gastric cancer, small cell lung cancer, for example. The relevance of many of these recommendations to breast cancer is questionable, to say the least. To apply them to individual patients outside the context of a clinical trial is hard to justify except in rare cases, but that’s exactly what Dr. Burzynski appears to be doing for large numbers of his patientss, picking off-label chemotherapeutic agents based on the results of this test and selling it as “personalized gene-targeted therapy” without letting patients know that (1) the evidence base behind these recommendations is often not relevant to the specific tumors being treated because it’s from different cancers; (2) the studies used to support these recommendations have a lot of uncertainty; and (3) most of these recommendations haven’t been validated in clinical trials.

Even worse, the very concept of “gene-targeted cancer therapy” hasn’t been convincingly shown to improve cancer outcomes, at least not yet. Believe it or not, I actually am in the camp who believes that eventually such a strategy will be proven useful and revolutionize cancer therapy, but that time is not yet. Gene-targeted cancer therapy is currently in its infancy and, except in rare situations outside of the existing currently validated biomarkers (such as HER2, ER, c-kit, and other genes for which targeted therapies exist) for the response of specific cancers, is not to be undertaken outside of the context of a clinical trial. In essence, Burzynski appears to be using such information on a “make it up as you go along” sort of fashion. Indeed, an e-mail from Renee Trimble confirmed this suspicion of mine when I pointed out to her that gene-targeted cancer therapy is in its infancy and that in the vast majority of cases we don’t know what to do with this information. I also wanted to know what the Burzynski Clinic was doing that is different from what the major cancer centers are doing. Her answer was, to put it mildly, unsatisfying, as I will discuss in the next section.

Compare and contrast

Before discussing how the Burzynski Clinic does personalized cancer therapy, I think it’s worth looking at how real scientists do it right now. In essence, real scientists use information of the sort provided by Caris Life Sciences or by their own genomic testing to stratify patients and identify them for clinical trials. An excellent example of this is a study hot off the presses in the November issue of Science Translational Medicine by a group from my very own alma mater, the University of Michigan entitled Personalized Oncology Through Integrative High-Throughput Sequencing: A Pilot Study. In essence, the investigators (Roychowdhury et al) began a pilot study to study the practical difficulties involved in using high-throughput sequencing in clinical oncology, which they identified in the introduction:

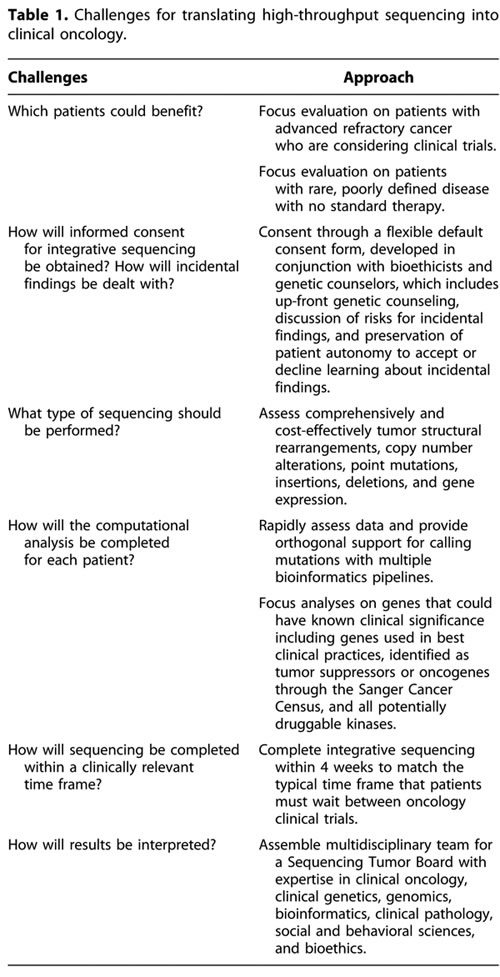

Translating high-throughput sequencing for biomarker-driven clinical trials for personalized oncology presents unique logistical challenges, including (i) the identification of patients who could benefit, (ii) the development of an informed consent process that includes a way to deal with incidental findings, (iii) the implementation of efficient and integrative computational pipelines for data analysis, (iv) the selection of the results that should be disclosed to patients, and (v) the completion of the sequencing analysis in a cost-effective and clinically relevant time frame (Table 1). We implemented an exploratory study that we call the Michigan Oncology Sequencing Project (MI-ONCOSEQ) to address these challenges.

The challenges, and the response of investigators, are well described in Table I:

Before undertaking this study in actual humans, in order to verify that their sequencing strategy would work, Roychowdry et al first grew in mice xenografts made from tissue taken from the tumors of two patients with metastatic prostate cancer. They performed their genomic analysis and found that one carried a common gene fusion found in prostate cancer and another previously undescribed gene fusion. They also found the androgen receptor gene was amplified and two tumor suppressors were inactivated. For purposes of the study, they set up a special tumor board to evaluate their findings and decide what clinical trials would be best for a patient. The authors then tried their strategy on two actual patients, one with colorectal cancer and one with melanoma. The tumor board suggested a combination of inhibitors that would be suitable for each patient on clinical trial. Unfortunately, at the time there were no appropriate clinical trials. This is the sort of preliminary work that needs to be done before genomic analysis of individual patient tumors, as will the implementation of clinical trials that patients can be assigned to based on their genomic information.

Other studies have tried to match genomic information gleaned from each patient’s tumor to individualized therapies with mixed results. One interesting approach was published about a year ago in the Journal of Clinical Oncology by a group from the Translational Genomics Institute (TGEN) led by Daniel D. Van Hoff entitled Pilot Study Using Molecular Profiling of Patients’ Tumors to Find Potential Targets and Select Treatments for Their Refractory Cancers, which uses an innovated, albeit controversial N of 1 trial design, with each patient serving as his own control. This summer, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center presented initial data at ASCO for over 1,000 patients in a phase I trial in which patients’ tumors were analyzed for genetic abnormalities and, when a drug existed to target that genetic abnormality, received that drug. Unfortunately, I didn’t go to ASCO this year; so I didn’t see the presentation, but the results are summarized on the M.D. Anderson Cancerwise blog:

For the 175 patients with one aberration, the medical response rate was 27% with matched targeted therapy. The response rate was 5% in 116 patients when treated with non-matched therapy.

Patients who received matched targeted therapy had median survival of 13.4 months, compared to nine months for unmatched targeted therapy. Median survival without cancer progression was 5.2 months for those receiving matched therapy, compared to 2.2 months for patients who received unmatched therapy.

True, this is not a home run by any means, but it suggests that “personalized” cancer therapy can improve outcomes.

Now let’s take a look at how the Burzynski Clinic does it, at least as far as I can figure out from my various sources and from Ms. Trimble. In response to my query about personalized gene-targeted therapy offered by the Burzynski Clinic, Ms. Trimble stated that a gene expression analysis is performed, as well as mutational analysis, FISH, immunohistochemistry for selected genes and that a blood test is also performed to measure the “concentration of proteins which are products of most important oncogenes.” How on earth they do this latter test, I really don’t know, because most oncogenes are not secreted proteins. Next, according to Ms. Trimble, the “medications which are shown to be best candidates for treatment, as well as those which are poor candidates, are identified from FDAs’ approved gene targeted medications and chemotherapy drugs list.” In addition, drugs are supposedly selected based on the patient’s clinical information, standard of care, FDA indication, data from phase II and III clinical trials. On the surface, up to this point it all sounded reasonable and not unlike what is being done at quite a few big cancer centers, hence my question (which was never answered to my satisfaction) of what Burzynski is doing that is different from (and presumably believed by Burzynski to be superior to) what everyone else is doing.

Then there was a hint. In addition, Burzynski then formulates a preliminary treatment plan that “will consist of medications which should cover approximately between 100 to 200 genes,” after sometimes doing a SNP analysis to “eliminate drugs which are not metabolized properly.” The result, or so it is claimed, is a set of drugs that have “synergistic activity which permits reduction of doses.” But why 100 to 200 genes? The very idea of targeted therapy is to hit the bare minimum of targets necessary to eradicate or control the tumor. Burzynski is going against the very concept of targeted therapy by making sure his therapy hits “100 genes,” a claim that resonates from what he said in the movie about him I reviewed last week. According to Ms. Trimble, “Antineoplastons and their prodrug, phenyl butyrate, are important ingredients of the combination because they cover the spectrum of approximately 100 genes.”

To support this claim, Ms. Trimble also sent me two papers from the Burzynski Clinic, both of which appeared in a journal I had never heard of before, the Journal of Cancer Therapy, which is clearly not indexed on PubMed because these papers never showed up when I searched PubMed for Burzynski. One described Burzynski’s approach for triple negative breast cancer (TNBC), the other for esthesioneuroblastoma and nonsmall cell lung cancer. What I found odd about both of these papers is that neither of them really examined whole genome expression profiling, although the paper about triple negative breast cancer did mention measuring the expression of “important” oncogenes. Meanwhile, the paper on esthesioneuroblastoma and nonsmall cell lung cancer primarily used sodium phenylbutyrate rather than any sort of gene targeting. The significance of this will become apparent in part III of this series, when I return to a discussion of antineoplastons. In the meantime, I note that, while the esthesioneuroblastoma is mildly interesting, it is a case report. I also note that the TNBC paper is a case report and small series in which a cocktail of targeted therapies plus chemotherapy appear to have produced somewhat durable responses. Unfortunately, in the absence of a control group or a clear prospective rationale for choosing these therapies, it’s hard for me to get too excited, particularly given that we don’t know the denominator; in other words, we don’t know how many patients with TNBC Burzynski has treated with this regimen who didn’t respond. We also don’t know the survival rates for these patients, only response rates.

It turns out that perhaps the best description of what “personalized” treatment means in Dr. Burzynski’s hands comes from the Texas Medical Board’s complaint against him, which can be found over at the Ministry of Truth or Casewatch. This complaint is based on the cases of two patients. First, here’s Patient A, who is described in the complaint thusly:

1. Patient A:

a. In approximately May of 2008, Patient A presented to Respondent with breast cancer that had metastasized to her brain, lung, and liver.

b. Respondent prescribed a combination of five immunotherapy agents – phenylbutyrate, erlotinib, dasatinib, vorinostat, and sorafenib-which are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”) for the treatment of breast cancer, and which do not meet the FDA’s regulations for the use of off-label drugs in breast cancer therapy.

c. In combination with the five immunotherapy agents, Patient A was prescribed capecitabine, a chemotherapy agent. The concurrent prescription of five immunotherapy agents in combination with a chemotherapy agent resulted in Patient A suffering unwarranted side effects.

d. Respondent owned the clinic pharmacy from which the multiple drugs were ordered. Respondent failed to affirmatively disclose to Patient A his ownership interest in the pharmacy.

This is what’s known as “throwing everything but the kitchen sink” at the tumor without any thought of interactions, as most of these agents have no proven role in the treatment of breast cancer. For example, erlotinib (brand name: Tarceva) is used to treat pancreatic cancer and non-small cell lung cancer. It works by inhibiting the tyrosine kinase of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and is not FDA-approved for breast cancer. However, it’s not unreasonable to think that it could work in breast cancer, as EGFR is believed to be important in some breast cancers, which is why this is an area of active research. Dasatinib (trade name: Sprycel) is also a kinase inhibitor. It inhibits the Src family tyrosine kinase. Vorinostat is a histone deacetylase inhibitor approved for use against cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Finally, Sorafenib is another tyrosine kinase inhibitor that inhibits the tyrosine kinases of different receptors, as well as raf kinases. The big problem with this sort of approach is that the more drugs you add, no matter how “targeted” they are, the more chance for interactions that increase toxicity, and throwing all these kinase inhibitors together in a cocktail with chemotherapy is a recipe for disaster, particularly because such cocktails haven’t been tested in proper phase I clinical trials to evaluate toxicity. They’re also all incredibly expensive as well, and Dr. Burzynski sells them through his own pharmacy.

Patient B appears to be the patient with esthesioneuroblastoma whose case report I described above. This is the relevant passage from the complaint:

Follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (“MRI”) scans were conducted in approximately August and December of 2003, and March of 2004, which showed progressive disease. Patient B was continued on phenylbutyrate during this 11 -month time period, and was not sufficiently informed about the drug’s lack of efficacy on her disease.

Which sounds rather unlike the glowing case report, now, doesn’t it?

Based on these cases, the Texas Medical Board accuses Dr. Burzynski of:

- failure to meet the standard of care;

- negligence in performing medical services;

- lack of diligence

- lack of informed consent;

- nontherapeutic prescribing;

- unprofessional conduct;

- off-label prescribing that does not meet standards for off-label use unless an exemption is obtained.

These are aggravated by:

- Harm to one or more patients;

- Economic harm to any individual or entity and the severity of such harm;

- Severity of patient harm;

- One or more violations that involve more than one patient; increased potential harm to the public;

- Intentional, premeditated, knowing, or grossly negligent act constituting a violation;

- Prior similar violations

If the Texas Medical Board’s charges are upheld, then this is how Dr. Burzysnki does “personalized, gene-targeted therapy.”

Compare how Dr. Burzynski does it to how U. of M. does it, or to how M.D. Anderson does it, and there is a world of difference. More than anything, the way Burzynski does it resembles a pale imitation of how how Steve Jobs did it, as he has nothing even approaching expertise and intellectual firepower of the experts whom Jobs recruited to help him and without the extend and breadth of data upon which those experts based their recommendations. Unfortunately, we all know what the end result of “trying to stay one step ahead of the tumor” using targeted therapy was in Jobs’ case. That’s because cancer is hard, and even when we think we know the intracellular signaling pathways that have been disrupted there’s usually a level of complexity beyond that which we don’t understand.

The cost

It’s very telling to look at the literature that Dr. Burzynski sends to prospective patients, one example of which is reproduced by Xeno. For example, rather than summarizing sound papers describing well-designed clinical trials, Dr. Burzynski only lists “response rates.” Looking at the table included in the literature, I noticed immediately that Dr. Burzynski says nothing about survival rates, only what he calls “objective response rates,” which are not defined in a meaningful way. The pamphlet defines them as as anything from an “improvement” (defined as “decrease in size of the tumors, not confirmed yet by the second follow-up radiological measurement”) to “complete disappearance of all signs of cancer. This is not how it’s done. There are standardized ways of measuring tumor response agreed upon by radiologists and oncologists, such as the RECIST criteria. Burzynski lumps all responses together in an oncologically meaningless way. Also remember, Burzynski often uses standard-of-care chemotherapy along with his antineoplastons; so we would expect some responses. The chart above, however, is virtually meaningless, if only for the simple reason that initial tumor response often doesn’t correlate to overall survival, and overall survival is what we care about. As Xeno also notes, the out-of-pocket costs are staggering. Contrast this to the clinical trials I mentioned above, where patients do not pay for the genomic profiling or chemotherapy.

As bad, Dr. Burzynski massively oversells what he is doing. For example, one patient writes:

The gene targeted approach makes sense to me, in essence what these doctors are doing is testing your blood and tumor samples, what they look for is genetic markers that tell them what receptors and or channels your tumors are using to grow. When they’ve identified these receptors and or markers they begin to prescribe off label medications to suppress the channels that are allowinng the tumors thrive.

If only that were what Dr. Burzynski were really doing under the auspices of clinical trials like the University of Michigan trial! And if only he weren’t charging patients massive amounts of money to do it, while telling patients things like this, quoted from Suzanne Somers’ book:

SS: When you talk about gene-targeted therapy, is that chemotherapy?

SB: No, this is not chemotherapy. Most of my patients have already had chemotherapy and it has not been effective for them. The beauty of antineoplastons is that they are natural compounds. They exist in our blood and form a protective system against cancer. You don’t expect to have toxic side effects from chemicals which are normal in your blood. And they cover a broad spectrum of genes, which means from the very beginning we have a much better chance to help this patient.

Of course, chemotherapy affects more than hundreds of genes; so by Dr. Burzynski’s criteria cytotoxic chemotherapy should be the best therapy of all because it affects the most genes!

As we have seen, Dr. Burzynski does indeed give chemotherapy to his patients. He combines that chemotherapy with a gmish of “targeted therapies” based on a commercially available but not FDA-approved gene expression profile test and calls it “personalized gene-targeted therapy.” Unfortunately, in my not-so-humble opinion, he doesn’t have a scientifically supportable rationale for combining his targeted therapies. Instead, skirting the line between science and pseudoscience, Dr. Burzynski gives every appearance of recklessly throwing together untested combinations of targeted agents willy-nilly to see if any of them stick but without having a systematic plan to determine when or if he has successfully matched therapy to genetic abnormality. In this, Dr. Burzynski does indeed resemble alternative medicine practitioners when they claim to “individualize” treatments. The result is that his outcomes are basically uninterpretable, making them useless for determining whether his approach works. At the same time, the cost is personal in terms of giving patients false hope and of unnecessary side effects for little or no benefit and financial in terms of bills that run from tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars charged to patients who are so desperate that they will pay them for even a glimmer of hope.

There is still one more issue to be explored in the strange case of Dr. Stanislaw Burzynski. My next installment will return to antineoplastons and, hopefully, close the loop on this tale.

The complete Burzynski series: