The saga of chiropractic began in 1895 when D.D. Palmer, a magnetic healer, announced that “95 percent of all diseases are caused by displaced vertebrae, the remainder by luxations of other joints.” Palmer opened the first chiropractic school in Davenport, Iowa, offering a three-week course of study at the Palmer School and Cure, subsequently renamed the Palmer School of Chiropractic. The school was taken over by B.J. Palmer, the son of D.D. Palmer, in 1906. In 1910, the course of instruction was six months. Kansas and North Dakota were the first states to pass laws legalizing the practice of chiropractic (in 1913 and 1915). By 1921, the Palmer School of Chiropractic, requiring 18 months of study, had 2,000 students, reaching a peak enrollment of 3,600 in 1922. By 1923, 27 states had chiropractic licensing boards. Hundreds of chiropractic schools sprang up, some offering correspondence courses. There were no entrance requirements, anyone could become a chiropractor. H.L. Mencken wrote in the December 11th, 1924, issue of the Baltimore Evening Sun:

Today the backwoods swarm with chiropractors, and in most States they have been able to exert enough pressure on the rural politicians to get themselves licensed. Any lout with strong hands and arms is perfectly equipped to become a chiropractor. No education beyond the elements is necessary.1

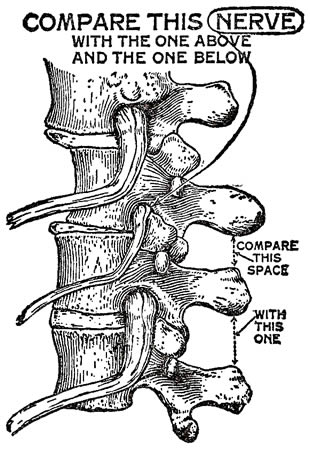

Although Palmer’s subluxation theory was contrary to all known laws of anatomy and physiology, the theory was appealing to the general public. Medical science was in its infancy, struggling to find effective and safe remedies for disease and infection. There was no known cure for many common ailments, and many of the medicines used by physicians were ineffective or harmful. In the public marketplace, the door was wide open for snake oil salesmen, entrepreneurs, and opportunists who could mix a concoction or fabricate a new treatment guaranteed to work. With growing numbers of chiropractors treating disease and infection by adjusting the spine to relieve alleged pressure on spinal nerves, offering treatment claimed to be superior to medical care, members of the medical community felt an obligation to oppose what they viewed to be blatant, unbridled quackery.

An old Palmer illustration showing how a displaced vertebra could cause disease by pinching a spinal nerve.

Morris Fishbein and the American Medical Association

By 1931, 37 states were licensing chiropractors. Chiropractic was gaining ground. In 1932, Dr. Morris Fishbein, the long-time editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association and an outspoken critic of chiropractic, wrote in his book Fads and Quackery in Healing that “…the fundamental dogma of chiropractic, that disease is caused by dislocation or subluxation of the bones of the spinal column, pressing on nerves, is simply a complete misrepresentation of the demonstrated facts.”2

A Report to the Medical Profession titled “Dear Doctor”, distributed by the Louisiana State Medical Society, advised physicians that chiropractors were engaged in the unlawful practice of medicine. “Medical men are opposed to chiropractic because it is baseless and disproved…Scientific medicine has accepted, approved and recommended only a part of what chiropractors do, and did so, in fact, before chiropractic was ‘invented.’ That part is physical therapy.” (The State of Louisiana did not begin to license chiropractors until 1974, the last state to do so, completing licensure of chiropractors in all 50 states.)

In June of 1946, an article in Reader’s Digest (“Can Chiropractic Cure?”) informed millions of Americans that “If you suffer from boils and bronchitis, from dysentery or diphtheria, you can find a chiropractor willing to ‘cure’ you by pressing your backbone and thus ‘adjusting’ an alleged ‘subluxation’ of some vertebra.”3

When it became apparent that medical and journalistic opposition to the practice of chiropractic had had little effect in curtailing public and political support for licensure of chiropractors, the American Medical Association formed a Committee on Quackery with the goal of containing and eliminating chiropractic as a recognized healthcare service. In November of 1966, the AMA House of Delegates adopted a resolution which stated, in part:

Chiropractic is an unscientific cult whose practitioners lack the necessary training and background to diagnose and treat human disease. Chiropractic constitutes a hazard to rational health care in the United States because of the substandard and unscientific education of its practitioners and their rigid adherence to an irrational, unscientific approach to disease causation.4

Chiropractors vs. the A.M.A.

In 1976, a group of chiropractors (Wilk et al.) initiated a law suit charging that the American Medical Association and associated groups had conspired to destroy chiropractic and to illegally deprive chiropractors of access to laboratory, x-ray, and hospital facilities. Most of the defendants settled out of court. On August 27, 1987, a United States District Court judge found the remaining defendants (the American Medical Association, the American College of Surgeons, and the American College of Radiology) guilty of restraint of trade by violating Sherman Antitrust Laws.

Conceding that chiropractic could be effective in treating certain kinds of back injuries and musculoskeletal problems, the court concluded that the American Medical Association had good reason to criticize chiropractic but should not have attempted to contain and eliminate an entire profession without first demonstrating that a less restrictive campaign could not protect the public. “There was evidence that the chiropractic theory of subluxations was unscientific,” the judge noted, “and evidence that some chiropractors engaged in unscientific practices.”5

Although the Federal Court ruled that the AMA was involved in illegal boycott and restraint of trade in its campaign against chiropractors, the ruling was not an endorsement of chiropractic treatment based on subluxation theory.

The yoke of subluxation theory

Clinging to the theory that gave it birth and independence, the chiropractic profession continues to define chiropractic as a method of removing nerve interference or correcting vertebral subluxations to restore and maintain health. State laws using vertebral subluxation theory to define and license chiropractors remain unchallenged. According to the National Board of Chiropractic Examiners in the United States:

The specific focus of chiropractic practice is known as the chiropractic subluxation or joint dysfunction. A subluxation is a health concern that manifests in the skeletal joints, and through complex anatomical and physiological relationships, affects the nervous system and may lead to reduced function, disability, or illness.6

Without mention of the word “subluxation,” the American Chiropractic Association offers this definition of chiropractic:

Chiropractic is a health care profession that focuses on disorders of the musculoskeletal system and the nervous system, and the effects of these disorders on general health.7

Chiropractic care based on an unproven subluxation theory that embraces a broad scope of ailments continues to provide justification for criticisms of chiropractic by the medical and scientific community, a criticism often referred to by chiropractors as “persecution.” A 2011 book written by a prominent chiropractor, The Medical War Against Chiropractors, The Untold Story from Persecution to Vindication, tells how persecution of chiropractors by the medical profession led to vindication for chiropractic when a federal court ruled against the AMA for restraint of trade in the Wilk vs. AMA suit8 ─ a ruling that offered no support for chiropractic subluxation theory.

The 19th century vertebral subluxation theory of D.D. Palmer continues to influence

public choice in health care.

Subluxation theory: Past, present and future

From the beginning, D.D. Palmer’s 1895 subluxation theory was criticized by medical practitioners who knew enough about the nervous system to know that subluxation of a vertebra or compression of a spinal nerve was not a cause of organic disease. Gray’s Anatomy, first published in 1858, revealed that the body’s organs were governed by the autonomic nervous system and not by spinal nerves, a fact denied by B.J. Palmer, one of the developers of chiropractic:

In the study of chiropractic, there is possibly no one point upon which we so radically differ, from all preceding schools, as in eliminating the so-called sympathetic nervous system. We shall endeavor, by quoting authorities, to show how much they are in the dark as regards the origin of ‘involuntary functions,’ and by so doing supplant it with a superior teaching of Chiropractic.9

Although chiropractic subluxation theory has evolved from a bone-on-a-nerve theory to a more complex description involving a “complex of functional and/or structural and/or pathological articular changes that compromise neural integrity and may influence organ system function and general health,” 10 the theory is no less implausible. Few of the 18 chiropractic colleges in the United States have discarded subluxation theory. “Despite the controversies and paucity of evidence the term subluxation is still found often within the chiropractic curricula of most North American chiropractic programs.”11

Currently, a chiropractic vertebral subluxation is being described as a “vertebral subluxation complex” which involves “changes in nerve, muscle, connective, and vascular tissues which are understood to accompany the kinesiologic aberrations of spinal articulations.”12

It seems likely that subluxation-based chiropractic, now described in many different ways, all alleged to restore and maintain health by removing “nerve interference,” will be perpetuated as a belief system. But I suspect that criticism by the medical and scientific community will eventually force a segment of the chiropractic profession to openly abandon subluxation theory and seek a new direction, as osteopathy did many years ago. Subluxation-based factions in chiropractic will always be around, however, to compete with evidenced-based chiropractors, requiring that each group be separately identified. Some observers feel that it is now too late for the chiropractic profession to seek changes that would allow it to provide services already being provided by mainstream health care, forcing the profession to embrace alternative medicine if it is to maintain its independence without subluxation theory.

Any practice that begins with a false premise and a founding father, such as chiropractic, homeopathy, and osteopathy, can never completely eliminate true believers who are bound together by the tenets of cultism. It will be necessary for health-care professionals and public health officials to participate in a never-ending campaign to inform the public about pseudoscientific practices that might be offered as an alternative to appropriate health care.

The decline of chiropractic

In the late 1950s, the Haynes Foundation in the State of California asked the Stanford Research Institute to conduct a study of chiropractic in California. This study was completed in 1960 and published under the title “Chiropractic in California”. (California, a state with the largest number of licensed chiropractors, has been licensing chiropractors since 1922. In 1989, there were 8,012 chiropractors in California!) “Chiropractors seek to restore health by adjusting body structures, especially the spinal column,” the study reported. Chiropractic was defined as “a system of therapeutics…based on the assumption that disease is caused by interference with ‘nerve force.'” The Stanford report concluded that the most realistic outlook for the future of chiropractic would be “The general continued decline of chiropractic as a profession in its present form.”13

When I published my book Bonesetting, Chiropractic, and Cultism in 1963, I suggested that a logical solution for the survival of chiropractic might be found in chiropractic specialization in the realm of physical treatment, in cooperation with science-based medical practice. I concluded that if the chiropractic profession fails to abandon subluxation theory and specialize in the care of back disorders, “…there will be no justification for the existence of chiropractic when an adequate number of medical specialists and medical technicians make scientific manipulation available in a department of medical practice.”14

Writing Bonesetting, Chiropractic, and Cultism, 1960

It has been 54 years since publication of Chiropractic in California, 51 years since the publication of Bonesetting, Chiropractic, and Cultism. While the chiropractic profession has survived and thrived in the 119 years of its existence, no credible research has been done by chiropractors to validate the chiropractic vertebral subluxation theory. Opponents of subluxation theory maintain that a simple review of anatomy and the autonomic nervous system provides enough evidence to forego serious consideration of the theory.15

Paradoxically, subluxation theory, categorized as a belief system in scientific literature, continues to define chiropractic in all 50 states despite higher educational requirements in chiropractic colleges. (Admission to a 4-year chiropractic college now requires a minimum of 3 years of undergraduate academic study.) It appears that chiropractic associations, representing the majority of chiropractors, might be reluctant to investigate subluxation theory or to seek a change in legislation that supports the licensure and livelihood of thousands of chiropractors.

As predicted by the 1960 Stanford study, support for the chiropractic profession in its “present form” now appears to be declining. Opposition to vertebral subluxation theory is increasing, and enrollment in chiropractic colleges has declined.16 The percentage of U.S. adults utilizing chiropractic services decreased from 9.9% in 1997 to 5.6% in 2006.17

A new approach: Integrative medicine

In what appears to be a survival mode, some chiropractic colleges are offering instruction in a variety of alternative healing methods, seeking shelter under the umbrella of alternative or integrative medicine. Southern California University of Health Sciences (SCUHS), for example, a former chiropractic college, is now offering degree programs in chiropractic, acupuncture, massage, Ayurveda, and oriental medicine.18 Functional Medicine University, sponsored by SCUHS, offers an online course of instruction in “functional medicine” which uses supplements, diet, and “other natural tools for restoring balance in the body’s primary physiological processes.”19 This shift to “integrative medicine” will allow chiropractors to treat a broad scope of non-musculoskeletal ailments as “primary care providers” without necessarily resorting to vertebral subluxation theory.

Mixing alternative medicine with subluxation theory in an “integrated practice,” the chiropractic profession has not renounced vertebral subluxation theory and has not made a concerted effort to specialize in conservative care for musculoskeletal problems. Inappropriate use of manipulation by chiropractors has generated increasing interest in the use of manipulation by physical therapists and orthopedic manual therapists who use manipulation only occasionally and only when appropriate.

There was a time when spinal manipulation was not readily available in departments of physical therapy, despite endorsement of such treatment in physical medicine textbooks. Chiropractors and osteopaths were often the only providers offering spinal manipulation. But this situation is rapidly changing. More physical therapists are being trained in the use of spinal manipulation, offering an alternative to chiropractic manipulation based on subluxation theory. Persons interested in studying or practicing manipulative therapy are being advised to pursue a Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) degree in order to avoid societal suspicion and the scientific alienation associated with the practice of chiropractic.

Unjustified criticism of spinal manipulation

Systematic reviews of the literature on the use of manipulation in the treatment of back pain indicate that spinal manipulative therapy may not be any more effective than other recommended therapies.20,21 But I suspect that further research will identify rare and special cases of mechanical-type back pain in which spinal manipulation might be the treatment of choice. Some back-pain patients simply prefer the pleasurable and relaxing effects of a good back-cracking back rub. Patient satisfaction coupled with the “possible” benefits of spinal manipulation is reason enough to support inclusion of spinal manipulative therapy as a treatment option in the armamentarium of any therapist or practitioner who treats back pain. It has been my observation that manipulation can be more effective than most forms of physical treatment in providing dramatic, albeit temporary, relief of mechanical-type back pain. Although acute back pain is usually a self-limiting condition, the symptomatic relief provided by spinal manipulation can be a welcome effect.

In rare cases, spinal manipulation may be a deciding factor in recovery from back pain. In acute back pain, for example, some manual therapists have proposed that a joint locked by muscle spasm caused by entrapment of synovial tissue or a cartilaginous fragment can sometimes be released by a single manipulation. Chronic back pain or stiffness caused by post-traumatic joint adhesions might require a course of high-velocity, low-amplitude thrust-type manipulation that moves spinal joints into the paraphysiologic space (past the normal end range of movement), reducing fixations by forcing slight separation of joint surfaces, often producing a popping sound (cavitation). In such cases, manipulation may be more effective than mobilization that simply moves joints within a normal range.

Needless to say, appropriate care for back pain depends upon a correct diagnosis, which will not always indicate a need for manipulation. Use of manipulation is considered to be inappropriate when based upon a “spinal analysis” done by a subluxation-based chiropractor who routinely “adjusts” the spine to correct “vertebral subluxations.”

Spinal adjustments vs. generic spinal manipulation

It is important to understand that a spinal adjustment used by a subluxation-based chiropractor is not the same as evidence-based generic spinal manipulation. A chiropractic adjustment used to correct a vertebral subluxation is a short-lever “specific” manipulation applied to a transverse or spinous process of a single vertebra in an attempt to move the vertebra and remove nerve interference in order to restore and maintain health. The treatment protocol of subluxation theory requires that all chiropractic patients have a spinal adjustment, whether they are symptomatic or not. Such an adjustment is sometimes done with a handheld instrument that uses a spring-loaded stylus to tap on a selected vertebra. Generic spinal manipulation, on the other hand, whether long lever or short lever, is a hands-on manipulation designed primarily to stretch muscles and loosen vertebrae in order to relieve pain and improve mobility; it is used only when indicated.

Unfortunately, appropriate use of generic spinal manipulation, which can be helpful in treating mechanical-type back pain, has been given a bad name by its association with chiropractic adjustments. Many chiropractors make good use of spinal manipulation when treating back pain, but use of manipulation to correct a chiropractic subluxation is increasingly being viewed as a fraudulent practice. (Remember that an asymptomatic chiropractic subluxation, alleged to be a cause of disease, has never been proven to exist and is not the same as an orthopedic subluxation that causes musculoskeletal symptoms.)

Long-lever manipulation designed to improve mobility

Bottom line

If the chiropractic profession as a whole does not renounce and abandon subluxation theory and make the changes needed to become a properly limited musculoskeletal specialty (possibly filling a niche as a subspecialty in conservative care for mechanical-type neck and back pain), with emphasis on appropriate use of manipulative therapy, justified criticism of subluxation-based chiropractic will continue to reflect upon the entire profession. In the meantime, back-pain patients who do not want to bother searching for a good back-cracking chiropractor who has renounced subluxation theory would probably have no trouble finding a physical therapist who uses manipulation appropriately. (Every state, the District of Columbia, and the US Virgin Islands now allow direct access to physical therapists for evaluation and some form of treatment without a physician referral.22)

References

- Mencken HL. Chapter 29: Chiropractic. Mencken. Vintage Books. New York, 1959.

- Fishbein M. The Basis of Chiropractic. Fads and Quackery in Healing: An Analysis of the Foibles of the Healing Cults with Essays on Various Other Peculiar Notions in the Health Field. Blue Ribbon Books. New York, 1932.

- Maisel AQ. Can Chiropractic Cure? Reader’s Digest. June 1946.

- Statement of Policy on Chiropractic Adopted by AMA House of Delegates. http://chirobase.org/08Legal/AT/amapolicy.html. (Accessed December 14, 2014)

- Getzendanner S. Memorandum opinion and order in Wilk et al. vs. AMA et al, No.76C 3777. U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division, August 27, 1987.

- Christensen MG, et al. Practice Analysis of Chiropractic. National Board of Chiropractic Examiners. Greeley, Colorado. May 2010.

- American Chiropractic Association. About Chiropractic. http://www.acatoday.org/level1_css.cfm?T1ID=42 (Accessed December 14, 2014)

- Smith JC. The Medical War Against Chiropractors: The Untold Story from Persecution to Vindication. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. 2011.

- Maynard JE. Healing Hands (Edited by B.J. Palmer). Jonorm Publishing Company. New York, 1959.

- Association of Chiropractic Colleges. Chiropractic Paradigm. http://www.chirocolleges.org/paradigmscopepractice.html. (Accessed December 14, 2014)

- Mirtz TA, Perle SM. The prevalence of the term subluxation in North American English-Language Doctor of Chiropractic programs. Chiropractic and Manual Therapies. 2011;19:14.

- Rosner A. The Role of Subluxations in Chiropractic. Foundation for Chiropractic Education and Research. Des Moines, Iowa. 1997.

- Stanford Research Institute. Chiropractic in California. The Haynes Foundation. Los Angeles, California. 1960.

- Homola S. Bonesetting, Chiropractic, and Cultism. Critique Books. Panama City, Florida. 1963.

- The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Quebec. The Scientific Brief Against Chiropractic. The New Physician. 1966. http://www.chirobase.org/05RB/CPSQ/00.html(Accessed December 14, 2014)

- Institute for Alternative Futures. The Future of Chiropractic Revisited: 2005 to 2015. Alexandria, Virginia. 2005.

- Davis MA, et al. Utilization and expenditures on chiropractic care in the United States from 1997 to 2006. Health Services Research. 2010;45(3):748-781.

- Southern California University of Health Services. http://www.scuhs.edu. (Accessed December 14, 2014)

- Functional Medicine University. http://www.functionalmedicineuniversity.com. (Accessed December 14, 2014)

- Rubinstein SM, et al. Spinal manipulative therapy for chronic low-back pain: an update of a Cochrane review. Spine. 2011; 36(13):E825-46.

- Rubinstein SM, et al. Spinal manipulative therapy for acute low back pain: an update of the Cochrane review. Spine. 2013; 38(3):E158-77.

- American Physical Therapy Association. FAQ: Direct Access at the State Level. http://www.apta.org/StateIssues/DirectAccess/FAQs/(Accessed December 14, 2014)

Sam Homola is a retired chiropractor who has been expressing his views about the benefits of appropriate use of spinal manipulation (as opposed to use of such treatment based on chiropractic subluxation theory) since publication of his book Bonesetting, Chiropractic, and Cultism in 1963. He retired from private practice in 1998. His many posts for ScienceBasedMedicine.org are archived here.