The BBC recently reported that a Guinean singer, Alama Kante, sang through her surgery in order to protect her voice. The reporting is unfortunately typical in that it emphasizes the seemingly amazing aspects of the story without really trying to put them into proper context. Specifically, the story emphasizes that hypnosis was used during the surgery, since Kante could not be placed under general anesthesia and still be able to sing, reporting:

The BBC recently reported that a Guinean singer, Alama Kante, sang through her surgery in order to protect her voice. The reporting is unfortunately typical in that it emphasizes the seemingly amazing aspects of the story without really trying to put them into proper context. Specifically, the story emphasizes that hypnosis was used during the surgery, since Kante could not be placed under general anesthesia and still be able to sing, reporting:

“The pain of such an operation is intolerable if you are fully awake. Only hypnosis enables you to stand it,” he was reported as saying by to French publication Le Figaro.

“She went into a trance listening to the words of the hypnotist. She went a long way away, to Africa. And she began to sing – it was amazing,” he said.

Reports of major surgery being performed using self-hypnosis or hypnosis instead of anesthesia crop up regularly, because of the obvious sensationalism of such stories. I reported a similar case from 2008, for example. At least in this case the news report gave the critical piece of information, often missing entirely from such reports:

The Guinean singer, who is based in France, was given just a local anaesthetic and hypnotised to help with the pain during the operation in Paris.

She was given a local anaesthetic. Local anesthesia, when properly done, can completely block all pain and sensations from the relevant area. Why was hypnosis even necessary, then? Perhaps it wasn’t, but hypnosis, self or otherwise, can be useful as a means of calming anxiety or distracting a patient from the procedure. Even with local anesthesia, a patient may still feel pulling and poking and this can cause anxiety.

Hypnoanesthesia might be a useful adjunct for surgical procedures where the patient is awake. The literature is not clear. But it is important to note how some define hypnoanesthesia – as “hypnosis, local anesthesia and minimal conscious sedation.” It isn’t certain what role hypnosis is playing when both local anesthesia and conscious sedation are given. In this case the BBC report did not mention conscious sedation either way, so we don’t know if the hypnosis had any pharmacological help.

It is also not uncommon for patients to medicate themselves prior to surgery, by taking some of their prescription pain or anti-anxiety medication.

Published research looking at hypnoanesthesia has been mixed, plagued by poor methodology and not carefully separating out hypnosis and an independent variable. Those that do have a higher tendency to be negative.

It should also be noted that hypnosis doesn’t really involve putting people in a “trance,” even though that word is commonly used (as with the current BBC reporting). Hypnoanesthesia is mainly a form a deep meditation, which can be self-induced or guided by another. The person is still awake and alert, and not what people might imagine from movies or television as “in a trance.”

This can be a useful technique for distracting patients from the procedure and any uncomfortable sensations and reducing anxiety. Such techniques are as old as medicine itself. Every medical student learns how to distract patients from a painful procedure, engage them in small talk, and to calm their anxiety. This is just good bed-side manner. Hypnosis or self-hypnosis is just a formalized way to do this, without clear evidence that it is superior.

The theme of mainstream reporting on surgery with hypnosis, however, generally paints a very different picture, for sensational effect – that of a patient in a trance while surgery is being performed on them with little or no anesthesia. This is a fiction.

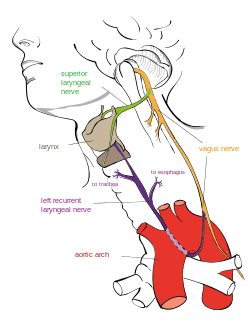

The other aspect of this story reported for sensational effect was that the patient, Kante, sang during the critical parts of the surgery to “save her voice.” The surgery was on the parathyroid gland. The risk with such surgery is damage to either the superior laryngeal nerve or recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN), which can cause hoarseness or loss of voice.

While the incidence of temporary or permanent paralysis of the RLN is quite low, 1-4%, it is a serious complication when it occurs. The greatest risk is from bilateral RLN injury, which can compromise breathing.

Monitoring the function of the RLN during surgery is not a new idea, and there are numerous studies looking at this technique. This involves stimulating the nerve and measuring a response (so that patients can be under general anesthesia). RLN stimulation is not perfect, but does highly predict RLN damage from surgery. It does not prevent the damage from occurring, however. Its primary use is to detect RLN damage on one side before proceeding to surgery on the other side, in order to prevent bilateral damage (on both sides).

Kante’s procedure apparently is unique in that singing was used to detect damage to the RLN, rather than nerve stimulation. It’s not clear if this was at all useful in preventing damage to the RLN, just demonstrating that damage had occurred.

Conclusion

This story is of a singer who had parathyroid surgery under local anesthesia and didn’t suffer a complication that occurs 1-3% of the time and could have damaged her voice. News reporting focused on the two aspects of this story that may have had little or no impact on the procedure, the hypnosis and singing as a way of detecting damage to the RLN.

It is not clear if hypnosis is at all beneficial, but it is plausible that hypnosis during procedures in an effective strategy of relaxation and distraction (although not necessarily more effective than any other method).

Singing during the surgery to monitor the RLN seems like little more than a gimmick. There is already a method in place to directly monitor RLN function and detect damage. It is also not clear if such monitoring reduces the incidence of damage to the RLN, or just predicts it.

The BBC, however, did not let educating their readers about all the relevant facts get in the way of telling a compelling narrative.