One common feature of pseudoscience is that proponents of a specific belief tend to exaggerate its scope and implications over time. In the world of physics this can eventually lead to a so-called “theory of everything” – one unifying theory that explains wide-ranging phenomena and displaces many established theories.

In medicine this tendency to exaggerate leads in the direction of the panacea, the miracle cure for everything. Why does this happen?

There are numerous examples. Here is a video of Bruce McBurney trying to sell his Precious Metals Nano Water to investors in the Dragon’s Den. The product is nothing but distilled water with a tiny amount of silver. McBurney claims that this magic water will essentially cure everything, all bacterial and viral infections, and even cancer.

The panacea is also not the sole domain of the lone crank. Straight chiropractors essentially believe that adjusting the spine can cure everything from bed wetting to asthma, and yes, even cancer.

What factors predispose to the panacea claim?

Theory of Everything

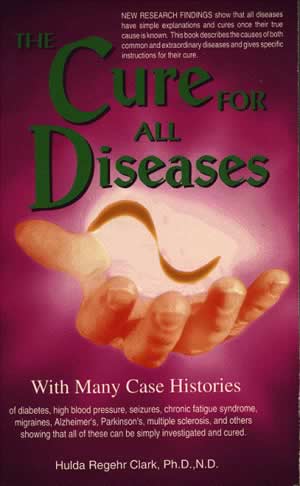

The cure for everything is partly related to the theory of everything. If all disease is caused by blockages in the flow of life energy through the spine, then all disease can be cured by adjusting the spine. In the case of Hulda Clark, all disease was allegedly caused by the liver fluke, and so treating that nasty scourge on humanity could therefore cure all disease.

In the era before science, when medical treatments were based on philosophy rather than an empirical understanding of the world, this approach was unavoidable. Galenic medicine believed that health and illness was a matter of the balance among the four humors, and so all conditions could be treated by bloodletting or purging. The Eastern version of this used acupuncture and cupping for bloodletting, which in the early 20th century was reworked as using needles to balance the life force.

Chiropractic and acupuncture have a similar history in that they began as healthcare theories of everything, but in the era of science are desperately clinging to legitimacy by claiming they improve subjective symptoms, those most amenable to placebo effects. Still, they retain their true believers, such as medical acupuncturists who will treat anything with acupuncture.

The scientific approach to health and disease has moved in the opposite direction from the theory of everything. The more we learn about the complexities of the human body, the more we discover all the many different ways that health can be affected. Every aspect of the biological machine can break down or not work optimally, causing illness. Causes may include genetic, traumatic, neoplastic, nutritional, degenerative, infectious, autoimmune, toxic, metabolic, environmental, biochemical, or physiological.

Modern medical theories of everything are maintained in two basic ways. The first is simply to deny modern science and everything that has been discovered about health and disease. This requires a profound level of scientific illiteracy, but this is unfortunately not uncommon.

The second method is to argue that, even though there may be many causes of disease, the body has an unlimited ability to heal itself. One thing keeps the body from perfectly healing itself, and so if you treat that one thing, self-healing will be restored – no matter what the problem. This is, for example, the subluxation theory of chiropractic. Subluxations block the flow of innate intelligence that, unhindered, would heal whatever ails you. This is precisely why alternative practitioners frequently tout that their treatments promote or enhance self healing.

Lack of scientific process

Even without the alternative philosophical underpinnings, there is a tendency for dubious treatments to undergo indication creep over time. A treatment that starts out being used for one specific indication has a growing list of conditions it can treat or cure, even conditions with very different real underlying causes.

This happens because the process that is being used to determine if the treatment works is flawed in the first place. Typically unscientific treatments are based upon anecdotal evidence, which is susceptible to placebo effects. Proponents are not being skeptical, nor are they conducting the kinds of studies that are capable of showing that the treatment does not work.

In fact the process they use is designed to show that the treatment does work. Therefore, no matter what they try it for, it will seem to work. They may naively come to believe that it works for everything. In some cases they may then backfill an explanation for why it works for everything, leading again to the theory of everything.

Essentially, if your beliefs and claims are disconnected from reality by the absence of a skeptical scientific process of investigation, then those beliefs will tend to drift off further and further into fantasy land.

Marketing

The final major factor is the simplest – marketing. If you have a product to sell, you want that product to have as wide a market as possible. In medicine this means as many indications for your treatment as possible. In fact, why limit your market at all? If your treatment works for every indication in every population, then you have maximized your potential customer base.

This does not necessarily mean that those selling panaceas are always knowingly lying, although in some cases that certainly seems to be true. Rather, there is a spectrum. There is a powerful motivation to believe that your treatment has wide-ranging implications. If you discover a treatment that is effective for some cases of athletes foot, that is an achievement and might even be highly profitable. But if you discover the treatment for all infections, or all cancers, or all human disease, then you should become world famous and fabulously wealthy. This is a powerful motivation to believe.

Even legitimate scientists fall prey to the allure of believing their discovery is bigger than it actually was. They have the rest of the scientific community to give them a reality check.

Companies also are highly motivated to exaggerate the indications and effectiveness of their products, and they need effective regulations that require scientific evidence to keep that trend in check.

In the world of alternative medicine and supplements, there is no reality check. The tendency to exaggerate claims is therefore unimpeded.

Conclusion

We have warned often on Science-Based Medicine to beware the “one cure for all disease.” The greater the claims for any treatment, the more improbable those claims become, and the greater should be the level of skepticism.

Biology is complex, and diseases have many causes. It is highly improbable that any one treatment will address a significant portion of human illness. Skepticism should also be high for any intervention that is claimed to address diseases or disorders that seem to have very different causes.

The “self-healing” gambit, while appealing, is also not realistic. Our bodies do have some ability to heal themselves. This ability to fight off infection, heal wounds, and compensate for illness can keep us going for many decades. The various systems of the body, however, break down in many ways, may be overwhelmed by an infection, can suffer trauma, or may have been suboptimal in the first place (such as with a genetic mutation). Entropy always wins out in the end.

We do not have an infinite ability to keep ourselves forever in perfect health. This is a religious belief that runs contrary to overwhelming scientific evidence. It’s a seductive belief, however.

The reality check of science may be disappointing to our emotional desires, but at the same time it has given us the actual ability to prolong life and improve quality of life significantly. I personally would never trade the hard-won knowledge of science for the comforting fictions of the cure-all.