Having spent many hours working in close proximity to a wall of vitamins, I’ve answered a lot of vitamin questions, and given a lot of recommendations. Before I can make a recommendation, I need to ask some questions of my own. My first is almost always, “Why do you want to take a vitamin?” The most common response I’m given is “insurance” – which usually means supplementation in the absence of any symptom or medical need. Running a close second is “I need more energy.” With some digging, the situation usually boils down to a perceived lack of energy compared to some prior period: last week, last year, or a decade ago. While I may identify possible medical issues as a result of these interviews (these are referred to a physician), I’m often faced with a patient with mild and non-specific descriptions of fatigue. And more often than not, they’ve already decided that they’re going to buy a multivitamin supplement. When it comes to boosting the energy levels, they’re often interested in a specific one: Vitamin B12 (cobalamin). So why does vitamin B12, among all the vitamins, have a halo of benefit for fatigue and energy levels? The answer is part science and a whole lot of marketing.

As has been described repeatedly SBM, multivitamins have an impressive aura of benefit and safety that, by and large, hasn’t been substantiated. Beyond the multivitamins, there are dozens of single-ingredient vitamins that contain doses that greatly exceed anything you can pack into a multivitamin, and usually significantly exceed the Reference Daily Intake. While these products may be appropriate for those that actually need a specific supplement (e.g., high dose folic acid, or calcium) they also increase the potential for unanticipated effects, giving a much higher dose than the typical diet can provide.

How the single-agent vitamins are consumed when self-selected by consumers seems to be influenced more by perceptions of efficacy, rather than the underlying scientific evidence. Vitamin C is associated with preventing colds and influenza (though it doesn’t work) and may be shelved alongside the other cold remedies. The B Vitamins are considered to be the “stress” vitamins, based on the perceptions that these vitamins are more rapidly depleted in people who are more “stressed”. Multivitamins like Stresstabs trade on this image. Among the B vitamins, B12 is often held out as as an almost miraculous energy booster. It’s often marketed as a sublingual product – you place it under your tongue, presumably for rapid, extensive absorption. It’s a claim hyped by supplement purveyors like Mercola, with his not-so-subtly-named “B12 Energy Booster” (warning, the video starts immediately):

If you often feel tired, run-down, and lacking in energy, you’re not alone. Low energy is one of our country’s biggest health complaints.

Some of the top reasons for this are:

- Refined foods sold in grocery stores are depleted of vital nutrients…

- Refined foods are loaded with sugar…

- Refined foods are full of chemicals…

- Refined foods are overloaded with food colorings; and…

- Refined foods are loaded with preservatives…

…but it doesn’t stop there, either.

Add the harmful effects of caffeine, pollution, conventional therapies, and the stress most of us experience everyday… and you’ve got yourself a recipe for energy drain.

Well, I’m here to tell you there’s a new way to give yourself extra energy.* Actually, a cutting edge way to feel more energized — without the jitteriness of caffeine.* More on this in a moment.

Now, of course, powering up with extra energy is just one of B12’s many health benefits*

(The asterix in the ad copy points to Mercola’s Quack Miranda warning)

It goes on and on, espousing the wonders of “microscopic nanodroplets™” and how it’s conveniently packaged “pre-metered, non-aerosol container that easily fits in your purse or pocket.”

Mercola’s is just one example. Searching “B12” and “energy” brings me 117 million results. If web hits were evidence, this is Cochrane-level persuasive. But let’s take a closer look at the rationale for B12 and the effect of supplementation – will B12 supplements give “extra energy” as Mercola promises?

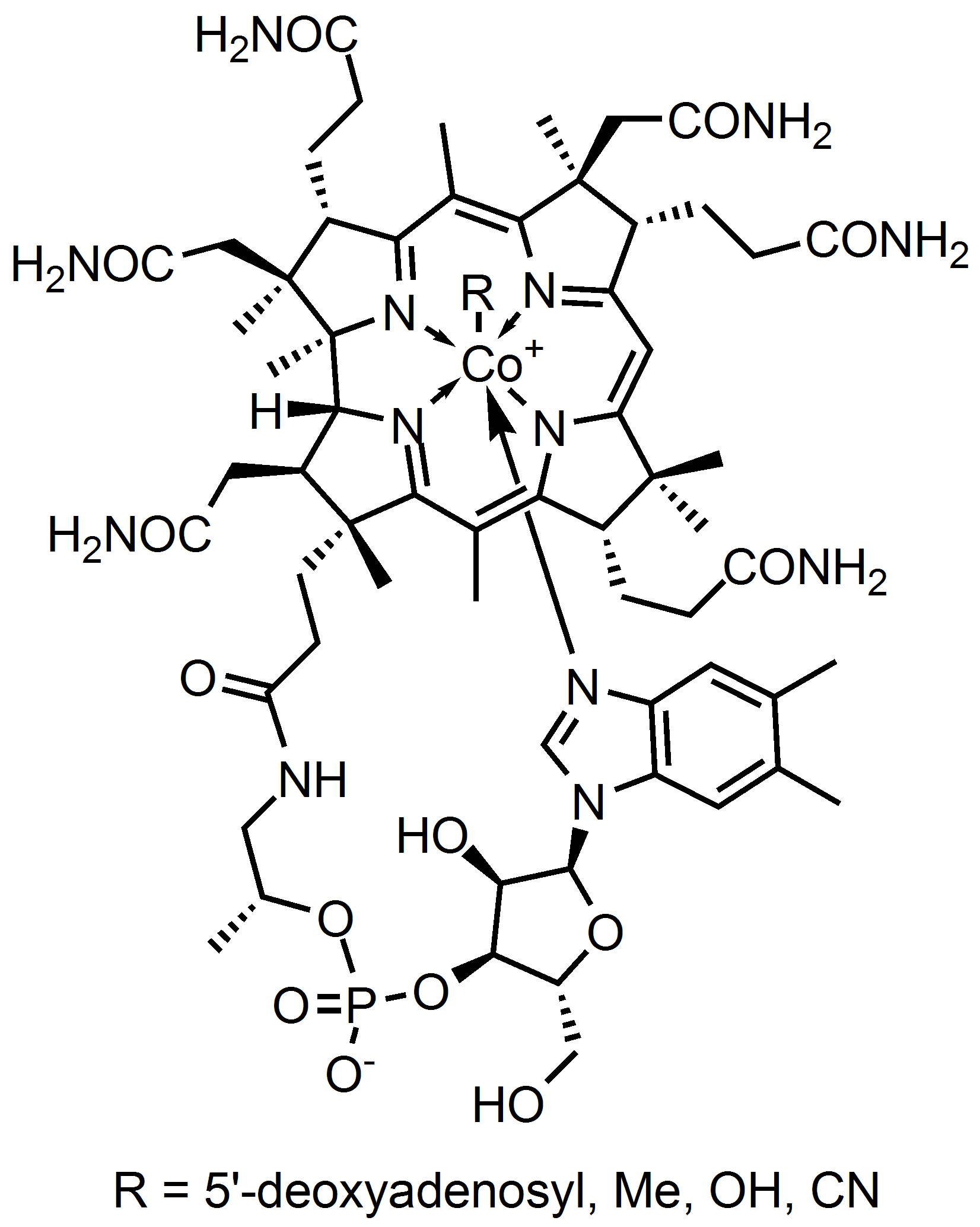

The Chemical

The history of vitamin discovery is fascinating and the identification of vitamin B12 is no exception. The result of a search for a treatment of pernicious anemia, vitamin B12 was initially thought to be the active ingredient in liver that supported recovery from blood loss. While the true active ingredient was iron, not B12, raw liver or liver “juice” (ugh) was a source of B12 and was the standard treatment for years. The vitamin was eventually isolated, and its molecular structure identified, by the 1950s. It was also identified that B12 is actually a group of very closely related chemicals, the cobalamins. Cyanocobalamin is the form that’s found in supplements and replacements; other forms include hydroxocobalamin and methylcobalamin.

While pernicious anemia is the classic sign of B12 deficiency, the vitamin plays an essential role in multiple pathways and systems, including the nervous system, where severe deficiency can lead to permanent damage. Where there are unexplained neurologic symptoms, such as paresthesias, numbness, or cognitive changes, particularly in the elderly, we might suspect deficiency.

We depend on our diets to provide B12. It’s naturally present in foods of animal origin: liver, clams, beef, and fish are excellent sources. Among manufactured foods, B12 is also fortified into products like cereals. Deficiency is due to one of three causes: malabsorption, insufficient intake, and other medical conditions:

Pernicious anemia is a consequence of an immune reaction that destroys the stomach’s ability to secrete intrinsic factor, which is essential for most of our B12 absoption. No intrinsic factor = little B12 absorption = pernicious anemia. Pernicious anemia can develop slowly, over decades – it’s most common in the elderly, and rare in those under 30.

Diet is the next common cause: Vegetarians and vegans that do not consume animal products must take a supplementary source of B12 – as supplements are yeast-derived, vegetarians are generally pretty responsive to advice and the justification for supplementation, which is particularly important in pregnancy. Outside of these groups, dietary deficiency is rare.

Other medical conditions can cause deficiency through a reduction in absorption, all of which may be more prevalent in older adults:

- gastritis and H. pylori infection

- intestinal effects and consequences of from gastrointestinal disease, cancer, or HIV

- reduced gastric acid secretion secondary to drug therapy like proton pump inhibitors

- other drugs, like the diabetes drug metformin, which can have gastrointestinal effects

Diagnosing deficiency in symptomatic patients includes measurement of serum vitamin B12. Unfortunately the test is somewhat limited in its usefulness, as it measures total, not active B12. Levels don’t correlate well with symptoms. There’s also overlap between what’s considered “normal” and “abnormal”, so deficiency can exist even when levels look “normal”. Different nomograms have been developed to support evaluation and treatment decisions. Where B12 deficiency is obvious, supplementation may be started without extensive investigations.

The Need for Supplementation

Deficiency is never the result of any short-term issue. The usual (non-vegetarian) “Western” diet provides 5-7 mcg of B12 per day, which is more than adequate to maintain appropriate levels: the RDA is 2mcg/day (2.6mcg/day in pregnancy). The total body stores are 2-5 milligrams, meaning that deficiency is the result of years of reduced intake – missing a day, a week or a month or more of any B12 consumption would not be expected to result in any clinically meaningful effects in someone with previously normal body stores.

Beyond preventing and treating B12 deficiency, supplements are consumed for a huge array of conditions: From the non-specific protection against “toxins” to infertility, depression, cancer, weight loss, kidney disease, Lyme disease and more. When it comes to demonstrated efficacy, B12 has only been conclusively established to be effective for preventing or treating B12 deficiency. There is preliminary evidence suggesting that B12 supplementation, in combination with folic acid, and pyridoxine reduces homocysteine levels. However it’s not as clear if lowering homocysteine levels reduces morbidity and mortality, as it may be a marker, rather than a cause, of disease. The evidence continues to evolve, and it’s not yet well established that treating elevated homocysteine levels with supplements is justified. There’s also some evidence to support B12 for reducing the risk of macular degeneration.

What about fatigue? In the deficient, yes, fatigue may be symptom of a B12 deficiency. But in those with normal B12 levels, the limited data on supplementation is not persuasive. The few investigations that have been conducted suggest that supplementing in the absence of a deficiency has no effect on fatigue.

Replacing B12

Beyond your basic tablets, there are sublingual sprays and wafers, and even intranasal administration. An injectable form of B12 is sometimes used, though oral supplementation is the general recommendation, except in cases of serious deficiency with obvious neurologic symptoms. Oral administration fof cases of malabsorption may sound counterintuitive. While oral absorption is limited, particularly in those with pernicious anemia, oral supplements do correct deficiencies – about 1% is absorbed even in the absence of intrinsic factor and stomach acid. (Oral supplements are typically 1000mcg, meaning at least 10mcg will be absorbed, adequate to meet daily requirements and replace body levels gradually. And despite Mercola’s hype, sublingual versions of B12 are no better than oral forms of the vitamin.

Most typical multivitamins contain 6mcg. This alone provide more than necessary for anyone that can absorb B12. Large doses, particularly oral forms, don’t appear to be harmful, and are well-tolerated. So supplementation as part of multivitamin “insurance”, or as a specific supplement, isn’t likely to harm.

Conclusion

While there is an important role for supplementing with vitamin B12 in some groups, high dose supplements to treat fatigue should be guided by a medical evaluation. For the energy seekers, supplementation in the absence of deficiency offers no benefits. Even in the deficient, B12 supplements won’t offer any sudden “boost” of energy: replacement and recovery takes time. Anyone concerned about their B12 intake should ensure they’re looking to dietary sources first. And for vegetarians and other at-risk groups, supplementing with B12 may be appropriate and science-based.