When you pick up a bottle of supplements, should you trust what the label says? While there is the perception that supplements are effective and inherently safe, there are good reasons to be skeptical. Few supplements are backed by good evidence that show they work as claimed. The risks of supplements are often not well understood. And importantly, the entire process of manufacturing, distributing, and marketing supplements is subject to a completely different set of rules than for drugs. These products may sit on pharmacy shelves, side-by-side with bottles of Tylenol, but they are held to significantly lower safety and efficacy standards. So while the number of products for sale has grown dramatically, so has the challenge to identify supplements that are truly safe and effective.

It’s been covered in depth before, but is worth repeating, that the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA) was an amendment to the U.S. Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act that established the American regulatory framework for dietary supplements. It effectively excludes manufacturers of these products from virtually all regulations that are in place for prescription and over-the-counter drugs, and puts the requirement to demonstrate harm on the FDA, rather than the onus on the manufacturer to show a product is safe and effective. The goal was to eliminate barriers to sale, and it worked: Within four years of the DSHEA, supplement sales grew from $4 billion to $12 billion. In Canada, the Natural Health Product regulations have had a similar effect at creating a manufacturer-friendly market: Pretty much anything goes, and today even homeopathic rabbit anus is deemed “safe and effective” by the Canadian regulator, Health Canada.

Notwithstanding the lack of good efficacy data for many products, the absence of good product quality standards is a persistent barrier to the science-based use of supplements. With drugs, the standards are rigorous: Any drug product that is approved for sale must be shown to be equivalent to the product studied in the clinical trials that established its efficacy. This allows us to extrapolate the findings from research into expected effects in patients. And manufacturers must meet stringent quality standards for their products, including verifying the consistency and quality of everything they produce. The same can’t be said for supplements. Even if there is promising data from studies, we can’t make the same inference about the expected effects. Lax regulations translate into lax product standards, and more questions about quality standards, safety, and expected effects. So even if I believe a supplement isn’t expected to interfere with someone’s prescription drugs, I’m basing this on the assumption the manufacturer is actually providing a product that delivers what the label says. And the different regulations mean we must have less confidence this is the case.

One of the more troubling signs that there are serious problems with the supplement market are the continued recalls and warnings from regulators. Just last week, Health Canada warned consumers about the following supplements with unlabelled contaminants (among many others):

- Snake Powder Capsule (for rheumatism) – actually contain piroxicam (an anti-inflammatory), dexamethasone (a steroid), hydrochlorothiazine (a diuretic) and cimetidine (used to treat ulcers). No snake though.

- Jia Rong Zhuang Gu Tong Bi Jiaonang (for joint pain) – actually contains indomethacin, piroxicam and diclofenac (all anti-inflammatories), prednisone (a steroid), hydrochlorothiazide, metoclopramide, theophylline (used to be used for asthma), trimethoprim (an antibiotic) and phenylbutazone (a now-banned anti-inflammatory which is associated with bone marrow suppression).

- Long Ren Tang Fu She Gu Rang Jiao Nang (for joint pain) – actually contains indomethacin, piroxicam, diclofenac, naproxen (yep, four NSAIDs), hydrochlorothiazide, cimetidine, metoclopramide and dipyrimadamole.

If you wanted to create supplements that not only had an irrational combination of ingredients, but also maximized the odds of potentially fatal adverse effect, you would have trouble topping the ingredients in these adulterated products.

The FDA maintains its own list, which has warnings that are equally frightening:

FDA continues to warn the public about Reumofan Plus—a product promoted as a dietary supplement for the treatment of arthritis, osteoporosis, bone cancer and other conditions. The product contains hidden prescription drug ingredients that can cause potentially fatal side effects. It could be labeled in Spanish and sold in some retail outlets, at flea markets and on the Internet.

Since June 2012, when FDA first warned the public about the dangers of Reumofan Plus and Reumofan Plus Premium, the agency has received reports of fatalities, stroke, dizziness, difficulty sleeping, high blood sugar levels, problems with liver and kidney functions, and severe bleeding in the esophagus, stomach and intestines, as well as corticosteroid (an anti-inflammatory drug) withdrawal syndrome.

Turns out after the recall, the manufacturer just relabeled it – it’s now called WOW, and still contains three undeclared prescription drugs: dexamethasone, diclofenac, and methocarbamol.

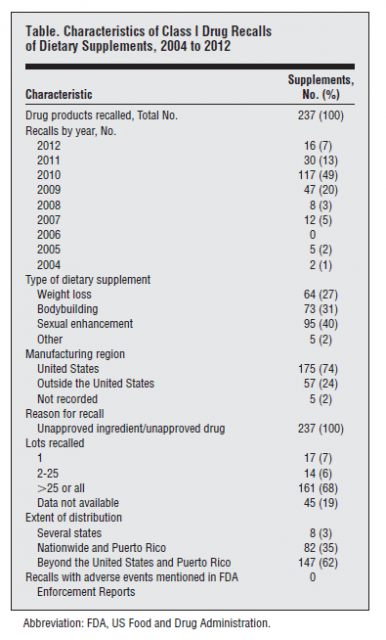

How frequently are supplements adulterated with real drugs? It’s a difficult question to answer given the lack of regulation of this market. The best signal may be regulator-initiated recalls. A systematic search was recently published by Ziv Harel and colleagues in JAMA Internal Medicine entitled The Frequency and Characteristics of Dietary Supplement Recalls in the United States, it’s a fairly simple review – a descriptive summary of all drug products listed as dietary supplements with class I (dangerous or defective product) recalls. While supplements are not drugs, once they’re identified to contain unapproved ingredients, they’re treated as unapproved drugs for the purpose of a recall. From the perspective of the supplement industry, the results should be concerning:

- Between 2004 and 2012, 465 products were subject to a class I recall. 51% were supplements – the balance were drugs.

- Most of the recalls occurred after 2008

- Every supplement recall was because of unapproved ingredients

- The majority of the recalled products were manufactured in the United States. Only 24% were imported.

- Supplements marketed for sexual enhancement were the most commonly recalled product, followed by bodybuilding supplements, and then weight loss products.

Remarkably, the authors noted that the FDA does not have accurate manufacturer contact information on file for 20% of all supplement manufacturers. What’s further, the FDA has found Good Manufacturing Practice violations to be present in nearly half of the firms it has actually inspected. So in light of the lack of regulatory oversight, it’s reasonable to think this list captures only a fraction of the total number of mislabelled and adulterated supplements on the market today.

There are few signals that can guide consumers. Sexual enhancement, weight loss, and body building supplements seem more likely to be adulterated. Given the lack of good evidence to suggest supplements are useful for these purposes, extra caution is warranted. While no harms were noted in the recall notices posted by the FDA, harms from adulterated supplements have been reported. Pai You Guo was a Chinese-manufactured weight loss supplement adulterated with two banned drug products, sibutramine and phenolphthalein. Despite warnings from the FDA, sales continued. In a survey, almost all users (85%) reported side effects from use.

Conclusion: Let’s help consumers, not manufacturers

A lowered regulatory bar for supplements and natural health products has been a boon to manufacturers, but the same can’t be said for consumer protection. In the absence of regulation that puts safety ahead of manufacturer interests, we shouldn’t expect to see any meaningful improvements in product quality, and the list of adulterated supplements will continue to grow. This double-standard has made it harder, rather than easier, for consumers to use supplements safely. Until a single, rigorous standard is applied across all consumer health products, there will continue to be uncertainty about the safety and quality of supplements.

Reference

Harel Z., Harel S., Wald R., Mamdani M. & Bell C.M. (2013). The Frequency and Characteristics of Dietary Supplement Recalls in the United States. JAMA internal medicine, PMID: 23589151